Off without a stitch

Urinary stones spell trouble for Lachlan the corgi, but a noninvasive removal procedure puts him back on the mend

Urinary stones spell trouble for Lachlan the corgi, but a noninvasive removal procedure puts him back on the mend

While preparing to move cross-country from the Twin Cities to Pennsylvania in October 2020, Karen Odash and her then 9-year-old Pembroke Welsh corgi Lachlan got quite the surprise.

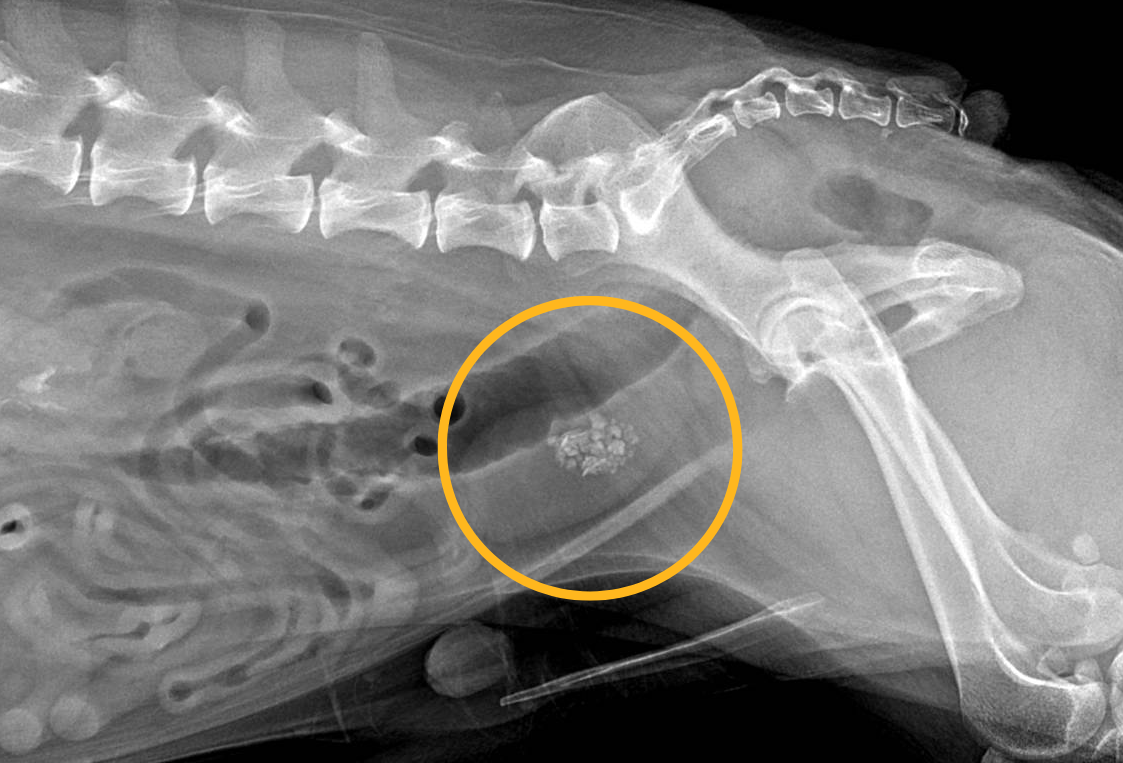

There, standing out from the darkness of an X-ray film was a bladder stone—a calcium oxalate stone to be specific.

“He had zero symptoms of it—none in any way, shape, or form,” Odash remembers.

Though Lachlan wasn’t showing any signs of distress from the stone’s presence, its large size was of concern. He and Odash were referred to the University of Minnesota Veterinary Medical Center (VMC) for removal.

The University also is home to the Minnesota Urolith Center, (MUC) a renowned facility that analyzes more than 89,000 urinary stones sent in from around the globe each year and is pioneering new and effective treatments for them. Calcium oxalate stones comprised 33 percent of samples submitted to the MUC in 2023.

“Calcium oxalate stones are one of the most common types that we see in dogs,” says Dr. Eva Furrow, co-director of the MUC and a clinician with the VMC’s Small Animal Internal Medicine Service. “They are a frustrating stone type because they are highly recurrent. They're complicated in terms of why they form. Part of a dog’s risk for calcium oxalate stones comes from their genetic background, and this can be difficult to manage.”

In Lachlan’s case, Dr. Jody Lulich, co-director of the MUC and a small animal internist at the VMC, treated Lachlan’s stones with laser lithotripsy. Laser lithotripsy is a minimally invasive procedure that uses a laser fiber to break up urinary stones into small enough pieces that can be removed or passed from the body without a surgical incision.

Lachlan’s treatment came in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, so Odash watched as veterinary technicians brought him into the hospital from her car for his procedure and didn’t see him in person again until he was discharged. His procedure went off without a hitch and a week later, she and Lachlan were settling into their new home in Philadelphia.

Though this stone was removed, Lulich recommended regular urinalysis to help prevent his bladder from forming more stones. Years later, when his regular veterinarian pushed on his bladder to retrieve a urine sample, something else came out—small objects akin to gravel. The sample went off to a familiar place with familiar results. The MUC confirmed that the objects were calcium oxalate stones.

When Odash inquired about removing the stones at veterinary clinics in Pennsylvania, the only option for Lachlan was cutting an incision from his belly button to his pelvis and surgically removing the stones.

“At this point, Lach was almost 12 years old,” she says. “He is a corgi. He is low to the ground, and I can't even imagine what recovery would look like for that.”

Unlike lithotripsy, which typically has patients discharged the same day and back to normal activity after 24 hours, recovery from traditional surgery can be painful and take weeks. Surgically removing stones is effective, but it can take a toll on a patient’s body, particularly if a dog has recurring stones.

“There's a 50 percent chance that calcium oxalate stones recur in two or three years,” Furrow says. “It can be a lot to go through bladder surgery every couple of years.”

Once again, Odash sought expert care at the VMC—now nearly 1,200 miles away. Working long distance with the hospital, she was provided with instructions to get Lachlan through his pre-procedure care before the pair hopped in the car and drove almost 19 hours back to Minnesota in September 2023. There, Furrow and Dr. Molly Doyle performed another laser lithotripsy on Lachlan and removed all his stones.

“They were able to get all of them out again without a single incision,” Odash says. “I got him home to the AirBnB that afternoon. And despite me trying to keep him under control, he put his leash in his mouth and was running down the street. I'm just like, ‘That's not the take it easy they were talking about.’”

While Lachlan was again living life stone-free, he also had been contending with other medical problems, including mobility issues and small masses in his liver. Less than three months after his lithotripsy, a trip to the emergency room spurred by Lachlan refusing to eat revealed a large tumor in his liver. Ultimately, Lachlan was unable to recover, and Odash chose to euthanize him.

Suddenly, the feisty dog she had known and loved since he was 8 months old was gone. Still, it brings her comfort to know in his last days he wasn’t experiencing pain from the bladder stones in addition to the cancer. In Lachlan’s memory, Odash highly encourages others to seek the expertise of the Veterinary Medical Center and Minnesota Urolith Center.

“I'm so grateful for the care that Lachlan received,” she says. “I can't recommend it enough. There are so many dogs that need this particular type of surgery, and I hope sharing his story and raising awareness about this can help them get that care.”