Pioneering relief

Preliminary results from a clinical trial show promise for improved treatment of painful urinary stones in cats

Preliminary results from a clinical trial show promise for improved treatment of painful urinary stones in cats

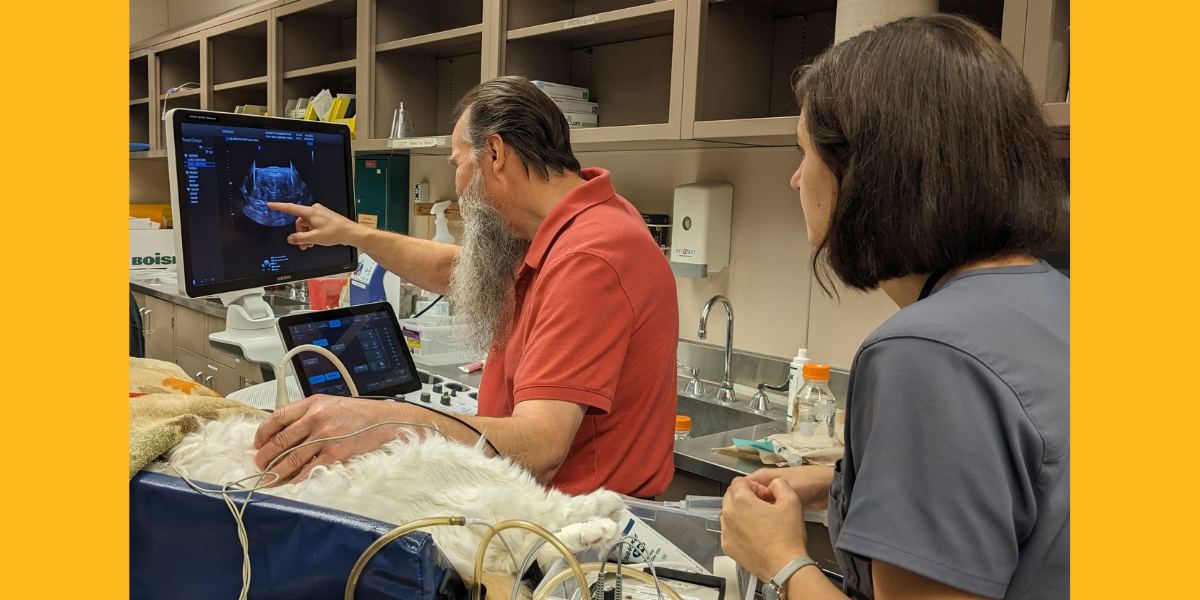

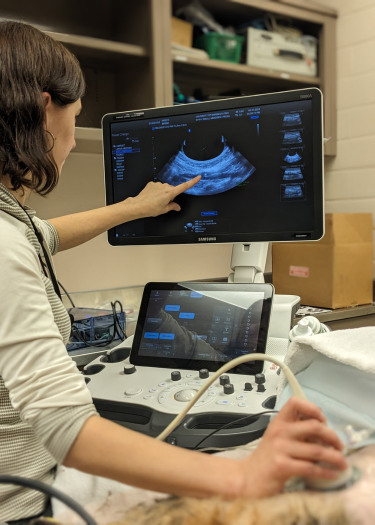

Veterinary Medical Center ultrasound technician Dick Hermes (left) locates a urinary stone inside a cat participating in the burst-wave lithotripsy clinical trial while Dr. Eva Furrow observes.

Kitty, Lecie, and Sox all lead separate lives in different parts of the United States, but two things unite them. They are cats that have experienced painful ureteral stone blockages, and they have seen improvements in their health after participating in a clinical trial testing a new treatment.

Ureteral stones form in the ureters, the tubes carrying urine from the kidneys into the bladder. In cats, these tubes are tiny at about 0.3 to 0.4 millimeters in diameter—about the size of a thick thread. When stones obstruct the ureter, they cause severe kidney damage and pose a significant health threat to cats.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota (UMN) College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) and the University of Washington have adapted technology used in people to cats in hopes it will help treat these stones without invasive surgery. A clinical trial testing the safety and effectiveness of the technology, known as burst wave lithotripsy (BWL), has wrapped up at CVM, under the direction of Drs. Eva Furrow and Jody Lulich, co-directors of the Minnesota Urolith Center, and small animal internal medicine resident Dr. Adam Hunt.

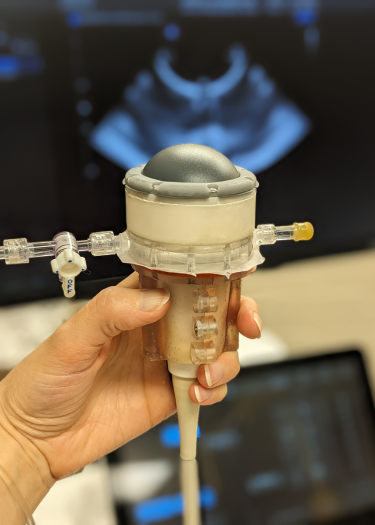

Burst-wave lithotripsy uses sound waves to break apart the ureteral stones from outside the patient’s body with no incisions. These smaller stone pieces are easier to pass through the ureter, into the bladder, and out of the cat’s body.

Furrow, the lead investigator of the trial, says the initial results look promising.

“We have found that burst wave lithotripsy seems to be a safe alternative to surgery,” she says. “We are seeing the stones break apart about 90 percent of the time and in around 60 percent of cases, we’re seeing the stones pass.”

While the trial’s data needs additional analysis and future trials will occur to further test and hone the capabilities of BWL, this trial’s preliminary outcomes are good news for cats and their owners whose only previous option may have been surgery.

Kitty, Lecie, and Sox were part of a 10-cat group that participated in the BWL trial, which was facilitated through the College's Veterinary Clinical Investigation Center.

Sox, who lives in Florida with her owners Ashley Santiago and Brennan McDonald, is typically a vocal cat—and a troublemaker—so when she became subdued and her urination seemed different, they rushed her to the vet.

“They did X-rays, and they found out that she was just kind of littered with kidney stones,” McDonald says. “We didn't really know what to do because, at the time, our vet couldn't tell that there was a stone that was outside of her kidney.”

When a kidney stone becomes lodged in the ureter, cats typically have two options, according to Furrow. The first is medical management, which can involve giving the stone time to pass on its own or administering medication to help it pass. The other option is surgery, the most common of which is called a subcutaneous ureteral bypass (SUB), which places an artificial ureter inside the patient’s body to restore urine flow. However, the surgery can be costly and comes with challenges afterward.

“The SUB devices can be life-saving but have complications in the long term because you’ve put this artificial implant into the cat for the rest of their life,” Furrow says. “They need maintenance. They can become infected. Mineral deposits can form inside the tube and become blocked. They can kink, they can migrate—that's rare, but there are things that can happen over time.”

When Lecie was first diagnosed with ureteral stones, surgery was an option presented to her owner, Nancy McGregor. While receiving emergency care at the UMN Veterinary Medical Center, Furrow reached out to McGregor to enroll Lecie in the BWL trial. While in the trial, she underwent two rounds of BWL treatment and her stones successfully passed in the days following her second treatment.

“I don't think I can express how grateful I am,” McGregor says. “They happen to have that machine, we happen to live in this city, and it was available for her when she needed it. Now, we have a pretty happy, normal-acting cat.”

There’s more work ahead for the UMN and UW researchers as they enhance the BWL prototype to allow for faster and more effective treatment. The current system also requires extensive setup and training, but Furrow hopes to see that streamline as the team continues its work.

“Our ultimate goal down the road is to get to the point where we have a nice system that is effective and as easy to set up and use as possible,” Furrow says. “We would like to make it widely available, so it could then be offered by veterinary clinics everywhere because, right now, our cats have limited options.”

Contributing to this research has been a meaningful experience for Kitty’s owners, Scott Brewster and Tony Jimenez. They traveled with her from New York City to Minnesota for the trial. After two rounds of BWL, Kitty’s stones didn’t pass during her time at CVM due to what Furrow believes may be scar tissue in the ureter, but the stones have fragmented enough for urine to pass through her ureters again.

“We believe this research is crucial because it offers a less invasive alternative to traditional treatments like kidney removal or SUB procedures,” Brewster says. “We're proud to have been part of Kitty's treatment and hope it contributes to helping other cats in similar situations.”

Sox’s owners share a similar sentiment. She also received two BWL treatments, which fragmented the stones in her ureters. X-rays taken in late July 2024 show Sox has no blockages in her ureters. She still has stones present in her kidneys but isn’t experiencing pain and is back to being her mischievous self.

“Even if the treatment wasn’t successful, I still know that they're one step closer to saving another cat,” Santiago says. “And I know how much we love Sox, and I'm sure somebody else loves their cat just as much. It just feels really good knowing that Sox’s treatment was successful, and the University of Minnesota will be able to help other cats along the way. It's very heartwarming, and I think about that often.”