Impact abroad

Dr. Whitney Waldsmith, '13 DVM, puts her veterinary expertise to work beyond borders as a member of the U.S. Army Reserve

Dr. Whitney Waldsmith, '13 DVM, puts her veterinary expertise to work beyond borders as a member of the U.S. Army Reserve

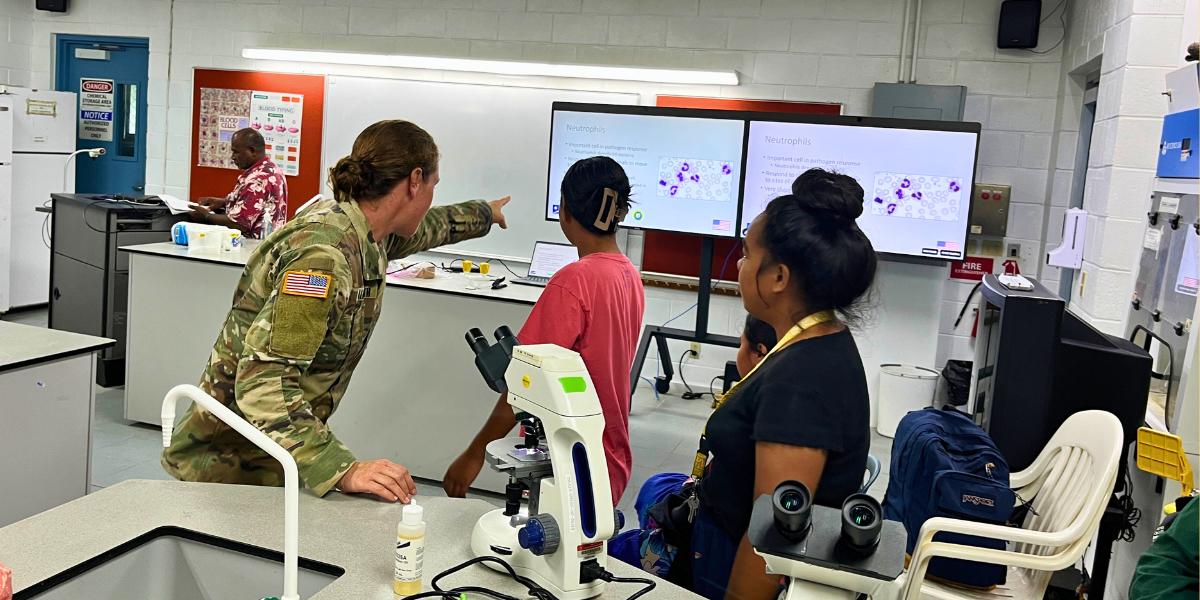

Dr. Whitney Waldsmith (left) meets with local college students in the Marshall Islands and uses the blood samples retrieved from local dogs as a teaching opportunity to give students an overview of blood biology, blood cells, bone marrow, and blood parasites.

A few times a year and thousands of miles away from the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), assistant professor Dr. Whitney Waldsmith can be found fulfilling her veterinary oath while serving her country.

As a member of the U.S. Army Reserve, she travels on missions, collaborates with international partners, and leverages her veterinary knowledge for projects focused on improving the health of animals and people while building systems and capacity in communities to help sustain it. This can include supporting systems for zoonotic disease detection and management, medical treatment and training, or investing in infrastructure to support all of the above

“I think a veterinary education is broadly applicable and extremely valuable,” says Waldsmith, ’13 DVM. “And what I've learned in traveling is that these systems dictate how we are able to practice as vets. And so understanding the larger systems and the impact of things like culture and economics have on how you practice, on how humans behave, and on where animals fit in society is really fascinating.”

Waldsmith is part of the U.S. Army’s Civil Affairs component, whose members work together with communities around the world to increase stability, enable local governments, and improve the quality of life for civilians.

These efforts include partnering with other military branches. Earlier this year and in years prior, Waldsmith participated in the Pacific Partnership, an expansive multinational humanitarian assistance and disaster relief mission coordinated by the U.S. Navy and conducted in the Indo-Pacific region, which covers the Indian Ocean and western portions of the Pacific Ocean.

“The goal for all of these missions usually is not to just come in, do stuff, and leave,” Waldsmith says. “It's to try to identify opportunities for development and then facilitate that through training or resource allocation with our host nation counterparts.”

Two of Waldsmith’s recent missions have taken her to the Marshall Islands and Palau. She and her team flew out to those locations and stayed aboard the USNS Mercy, one of the Navy’s two 1,000-bed hospital ships outfitted with modern medical facilities. The ship serves as a base for Pacific Partnership operations.

Located between Hawaii and the Philippines, the Marshall Islands is a small country home to about 42,000 people. With no veterinary services available on the island, a nongovernmental organization coordinates with the U.S. to bring in veterinary professionals to conduct spay and neuter events. Waldsmith’s group joined those efforts, drawing blood and taking fecal samples from animals to test them for parasites. The information gained from the testing seeks to paint a clearer picture of the presence of zoonotic disease on the island and was shared with government officials.

Waldsmith and others also met with local college students and used the blood samples as a teaching opportunity, giving students an overview of blood biology, blood cells, bone marrow, and blood parasites.

Next up was Palau, a small island country located about 950 miles east of the Philippines with a population of about 18,000 people. It has limited veterinary services in the form of a private clinic, a grass-roots spay and neuter group, and a state-run shelter facility. On this mission, Waldsmith’s group taught diagnostic skills such as blood testing and urinalysis to shelter staff with an emphasis on zoonotic disease detection.

Additionally, the group worked with police K-9 handlers on best practices for managing working dogs.

As part of the trip, Waldsmith also attended a One Health conference put on by a Navy environmental health officer that included components touching on veterinary medicine, infectious disease, and agriculture and allowed her to forge connections with people across the island and the Armed Forces.

The knowledge she gains doesn’t stay inside her head for the next mission. Waldsmith also incorporates these lessons learned into classes she teaches at CVM and when advising students involved in community medicine outreach at the college. Veterinary students are often taught the “gold standard” of care, which relies on access to high-quality equipment and facilities—which can create barriers for communities without the resources to provide and pay for this level of care.

Finding solutions that are feasible for under-resourced communities requires creativity—an important tool for veterinary students to learn to wield no matter what their career paths.

“I think it's valuable to learn to think outside that box because I didn't take advantage of all the opportunities to do that when I was a student,” Waldsmith says. “I came out of school pretty focused on and enthused about animal medicine. Once I started learning about international systems and all of the factors at play, I realized how interesting and important it is to integrate these elements into medicine. I want students here to have the opportunity to recognize that before they graduate.”