'I matter to me'

CVM alumni and faculty share experiences, challenges, and advice that have shaped their lives and work as part of a Black History Month event

CVM alumni and faculty share experiences, challenges, and advice that have shaped their lives and work as part of a Black History Month event

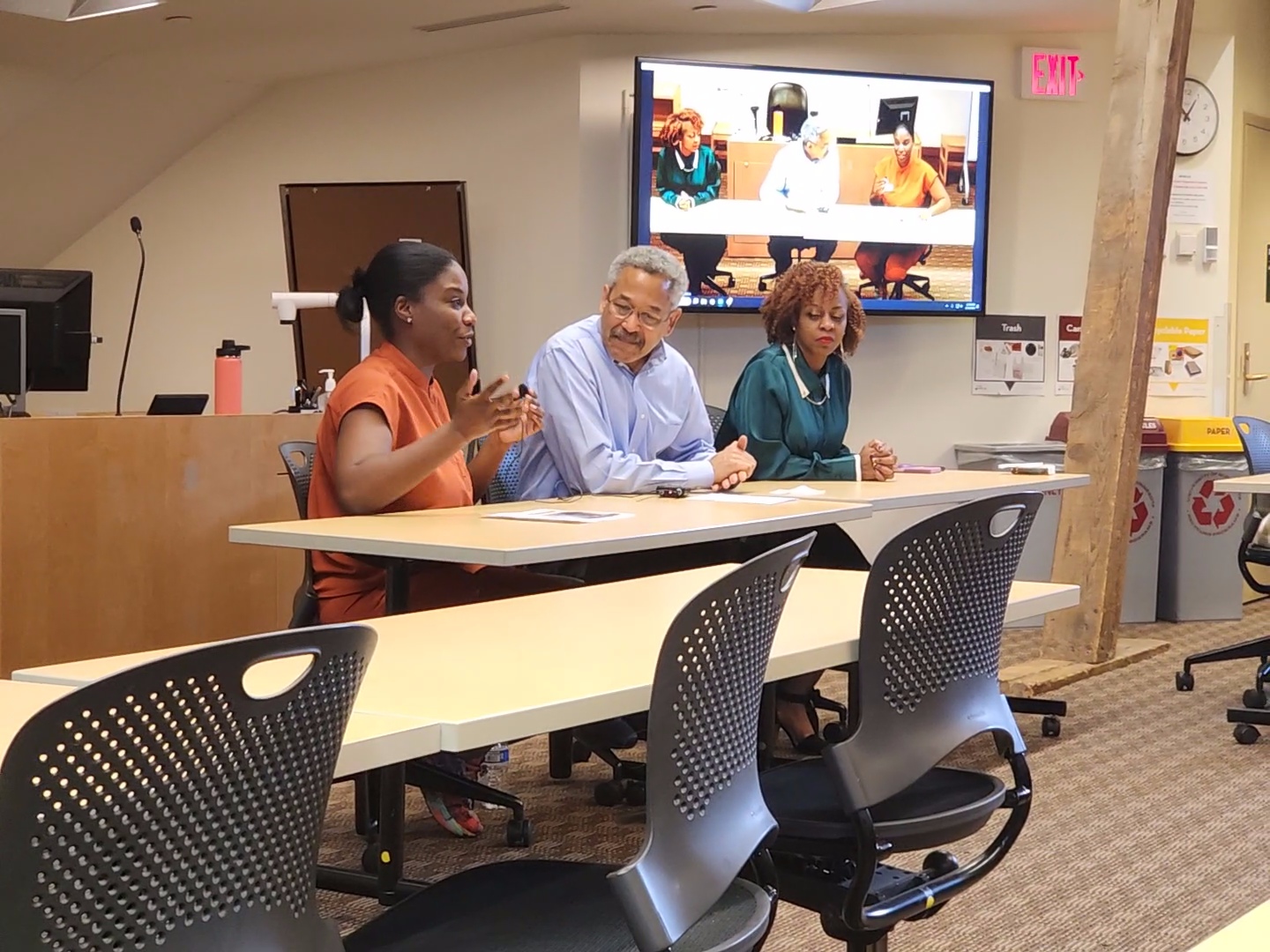

(Left to right) VOICE Public Relations Chair Calah Sewell, VOICE Vice President Zynia Alvarez, Dr. Stephan L. Schaefbauer, Dr. Jody Lulich, Dr. Abigail Maynard, and VOICE President Courtney Labé.

There aren’t many people in the veterinary field who look like Drs. Jody Lulich, Abigail Maynard, and Stephan L. Schaefbauer. In fact, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates only 1 percent of the nearly 90,000 practicing veterinarians in the United States identify as Black.

In mid-February, the University of Minnesota VOICE (Veterinarians as One Inclusive Community for Empowerment) Chapter invited Lulich, Maynard, and Schaefbauer to share their experiences while pursuing professional and education careers within veterinary medicine through a Black History Month Panel at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

The panelists answered questions from organizers and from the audience, several of which centered around the themes of representation and othering—the practice of treating people as though they are not part of a group.

With so few Black peers in the field, all three panelists agreed there is pressure to represent and constantly be on point in their work.

“The most important thing to do is show up,” says Lulich, a professor of internal medicine and co-director of the Minnesota Urolith Center. “And after you show up, the most important thing to do is to be your best. And that's what I try and do.”

Showing up is challenging when Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are faced with pressure to tone down aspects of their appearance, demeanor, and cultural expression and values. Schaefbauer, an area veterinarian in charge at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, says it took time for her to be comfortable showing up as her true self in a professional setting.

“I've learned to appreciate me for me for the sake of me, and not for the sake of what others think about me,” she says. “I came into my own a little bit better. I can walk in a room and stand on my laurels and show up as me.”

Maynard, a partner doctor at Hometown Veterinary Partners who also serves on the board of the Minnesota Board of Animal Health, is originally from Barbados and came to the U.S. for her fourth year of veterinary school to complete clinical training. Adapting to a new country and now working in a racially homogenous field has come with challenges, but Maynard says she gives herself grace and puts her focus on doing the best work she can in a way that prioritizes her happiness and comfort.

“I matter to me. I'm going to do what I need to do to be comfortable for me because my comfort matters. And it doesn't mean that I am losing my culture or that I am not being thoughtful of my culture,” Maynard says, noting examples such as slightly changing her accent or taking on a more reserved demeanor. “That's okay because it's not a different person. I’m still Abby, just a version of Abby that I need to be for me to be comfortable—and that's what I think matters most.”

When it comes to inspiring the next generation of BIPOC veterinarians, the panelists emphasized that they and their peers all play important roles. Staffing shortages, long hours, and compassion fatigue all contribute to burnout in the veterinary profession. Still, Schaefbauer urges her peers to find time to connect with and guide students interested in a veterinary career.

“We each have the ability to pour into a child—whether it's a child of color or any child—to make our profession better for the future,” she says. “We may not be able to bring in hundreds at a time, but one is OK. If each one of us brings in one, if each one of us encourages one, that's enough.”

Planting seeds early is key to this work, according to Maynard, as well as encouraging students to not let where they come from dampen their aspirations.

“I’m going out to schools in my free time, and I’m talking with these children and letting them know that I am a nobody from nowhere,” she says, “and if I can do it, they can do it.”

But presenting BIPOC students with the opportunity to pursue veterinary medicine is not enough, Lulich says, noting students may need support such as financial assistance and mentorship. It’s up to veterinary college administrations to build systems that set students up for success.

“They need to offer the opportunity and then navigate for success—don’t just drop us the opportunity,” he says. “They need to make sure that we have the means to move forward and move on in order to make it work.”