The cornerstone of health and wellness

Veterinary nutritionist Julie Churchill satiates the public’s craving for pet dietary health

Veterinary nutritionist Julie Churchill satiates the public’s craving for pet dietary health

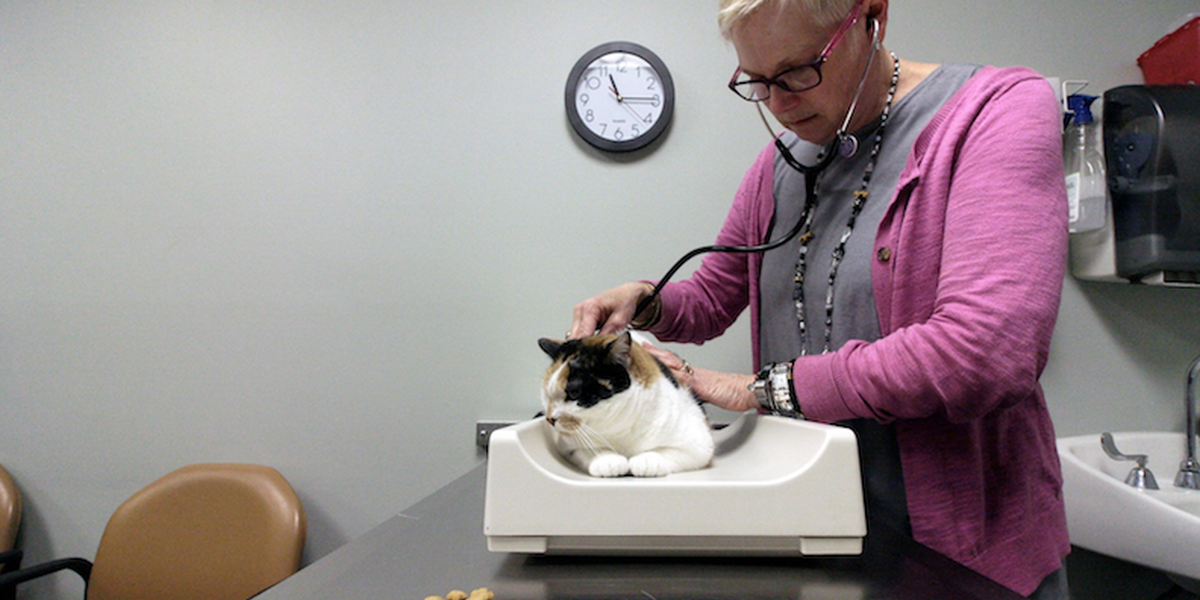

Contessa, a 10-year-old calico that was adopted as a young stray, has been seeing Nutrition Services at the Veterinary Medical Center for a variety of treatments since Churchill first developed a nutrition plan for Contessa in 2015.

Julie Churchill was destined to become a veterinarian. To those who knew her as the little girl who devoured James Herriot books and routinely brought home injured animals, her career path came as no surprise.

“I liked to help any critter in need,” Churchill, DVM, PhD, DACVN, says. “I would rescue stray cats and dogs, injured birds, squirrels, snakes, or any hurt animal from the forest. My parents couldn’t use their bathtub for a month because I had a turtle with a broken shell in there.” Churchill briefly attended nursing school, looking to deliver primary care to underserved areas. “But in the end, I always knew I wanted to be a vet.”

Today, Churchill, a veterinary nutritionist and associate professor in the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, is a trusted source of knowledge for the pet owners in her clinical practice, students at the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), and, increasingly, other veterinarians across the country.

She’s a leading authority in a specialty that’s only existed since 1988. There’s no physician corollary to the veterinary nutritionist in human medicine, Churchill says, and there are fewer than 100 board-certified veterinary nutritionists in the United States. It’s a field with lots of opportunity, she adds. “Many veterinary colleges do not have a veterinary nutritionist.”

Churchill, who also completed a residency in small animal internal medicine, is often consulted for local, state, and national media on pet food, nutrition, and diseases. When news broke last year that the FDA was investigating a possible link between grain-free dog food and a heart disease called dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), pet owners panicked. Churchill was contacted by numerous media outlets about the issue and collaborated with board-certified veterinary cardiologist Michelle Rose, DVM, DACVIM, director of medical specialties at the Animal Emergency and Referral Center of Minnesota, to offer continuing education throughout the state.

DCM is a disease that affects the heart muscle’s ability to pump blood and can ultimately lead to congestive heart failure. While it’s known to affect certain dog breeds, DCM has been showing up in other breeds historically not prone to it. And in most cases, the affected dogs have been on boutique, exotic, or grain-free (often called BEG) diets.

“I’ve been disappointed in the way pet food is marketed and the industry’s response. Rather than seeing this as an opportunity to educate people, they produced more and more grain-free foods because there was a demand.”

Julie Churchill, DVM, PhD, DACVN

The reason for the link is still unknown. “While it’s been portrayed as simply a grain-free-food issue, it’s broader than that,” Churchill says. Researchers speculate that the culprit may be an ingredient used to replace grains in pet foods, such as kangaroo, bison, or lamb meat as well as lentils, chickpeas, or sweet potatoes. The nutritional value of these ingredients is less known—they could be low in essential nutrients. Another possible cause could be the combination of these ingredients reducing the digestion and availability of nutrients important for normal canine heart function. In the meantime, Churchill is suggesting that since there’s no proven benefit for BEG diets, it’s safer for owners to choose other options.

The rapid rise of grain-free and exotic pet foods is the product of a “perfect storm,” Churchill says. Factors include the melamine pet food recall in 2007, which involved intentional adulteration of a pet food ingredient from China; human food trends like Atkins, Paleo, and other low-carb diets; a strong desire to provide the best food; and a misconception that food allergies are common, when they are in fact quite rare. All of these factors point to a need for better, clearer, more widely shared information about pet nutrition.

“For me, nutrition is the cornerstone of health and wellness. I’m passionate about that,” says Churchill. “I’ve been disappointed in the way pet food is marketed and the industry’s response. Rather than seeing this as an opportunity to educate people, they produced more and more grain-free foods because there was a demand.” Whether it was intentionally done or not, this action promoted the belief that grain-free diets were somehow nutritionally better.

Churchill has never recommended grain-free food because, she says, she never saw a reason to do so. “I’m very particular about the foods I recommend for my patients and for my own pets. Grain-free hasn’t been in my repertoire.”

That BEG diets are inherently healthier for pets is among many nutritional myths Churchill works to debunk in her patient care, teaching, and advocacy roles. Another myth: that “processed” food should be avoided.

“You and I are taught to avoid processed foods—to shop around the perimeter of the grocery store and buy fresh produce and whole foods. But the motivation for processing human food is different. It’s usually to increase shelf life, to make it more economical, and to make it tastier. Sugar, fat, salt,” Churchill says. “Dog and cat food is formulated to be complete and balanced as it’s the whole diet your pet consumes. It’s processed to meet the goal of providing everything they need—when fed in the right amounts.”

Speaking of which, Churchill has been sounding the alarm on pet obesity. According to the Association for Pet Obesity Prevention, some 60 percent of cats and 56 percent of dogs in the United States are currently overweight or obese. “Obesity can lead to arthritis, cancer, metabolic disease, and heart and lung disease in both dogs and cats, and diabetes in cats,” says Churchill. “It’s an epidemic, and it’s preventable.”

Churchill is championing the body condition scoring (BCS) system, a 9-point assessment tool that can help pet owners discern when their animal is healthy and when they are becoming overweight. A BCS of 1/9 is emaciated, while a score of 9/9 is obese. “We should strive to have pets maintain a 5 out of 9 body condition score to promote health,” says Churchill. “You should be able to easily feel—but not see—the ribs of a dog or cat who’s a healthy weight and BCS.”

Together with North Carolina veterinarian Ernie Ward and UK veterinarian Alex German, Churchill is working on standardizing the BCS, the universal definition of obesity, and the classification of obesity as a disease. Last year, they succeeded in getting the Future Leaders of the American Veterinary Medical Association to support a position statement to that effect, slated for publication in JAVMA, the association’s clinical journal. “We’ve had 22 veterinary organizations across the globe sign on as endorsers, and we’re not stopping,” Churchill says. “I’m on a mission.”

Among the most gratifying ways Churchill helps promote pet health is through her work in the classroom, where she strives to cultivate clinicians who understand “that nutrition matters and can positively impact pet health,” she says. “I try my best to make topics relevant and practical, and to provide as many resources as possible for them to use later in practice. It’s easy to find real-life examples because all pets eat.

“The opportunity to teach was one of the biggest draws for me to pursue an academic career,” Churchill adds. “It resonates with a core value of a servant leader: to help others achieve their best. It’s a great privilege to be a teacher.”

“The opportunity to teach was one of the biggest draws for me to pursue an academic career. It resonates with a core value of a servant leader: to help others achieve their best. It’s a great privilege to be a teacher.”

Julie Churchill, DVM, PhD, DACVN

Prevention is the ultimate goal. Churchill wants to help empower all veterinarians to make informed and tailored dietary recommendations for each of their patients—thereby stopping unhealthy weight gain and obesity and other health problems before they start. “The public is craving nutrition expertise,” Churchill says. “I think we’ve abdicated that role for too long. I want to help practitioners be the nutritional experts that their patients need—every practitioner should feel confident and competent in making a specific food recommendation.”

Photos by Nathan Pasch