- Issue:Published:Photo(s) by:USDA, Bennett Graham Abrahamson

In the next three decades, the global food supply will need to feed an additional 3 billion people. The food system is already deeply intertwined with animal health and people around the world are adding more animal by-products to their diets. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), annual meat production is projected to increase from 327 million tons in 2016 to 370 million tons by 2028 with the most growth in developing countries where animal health is challenging.

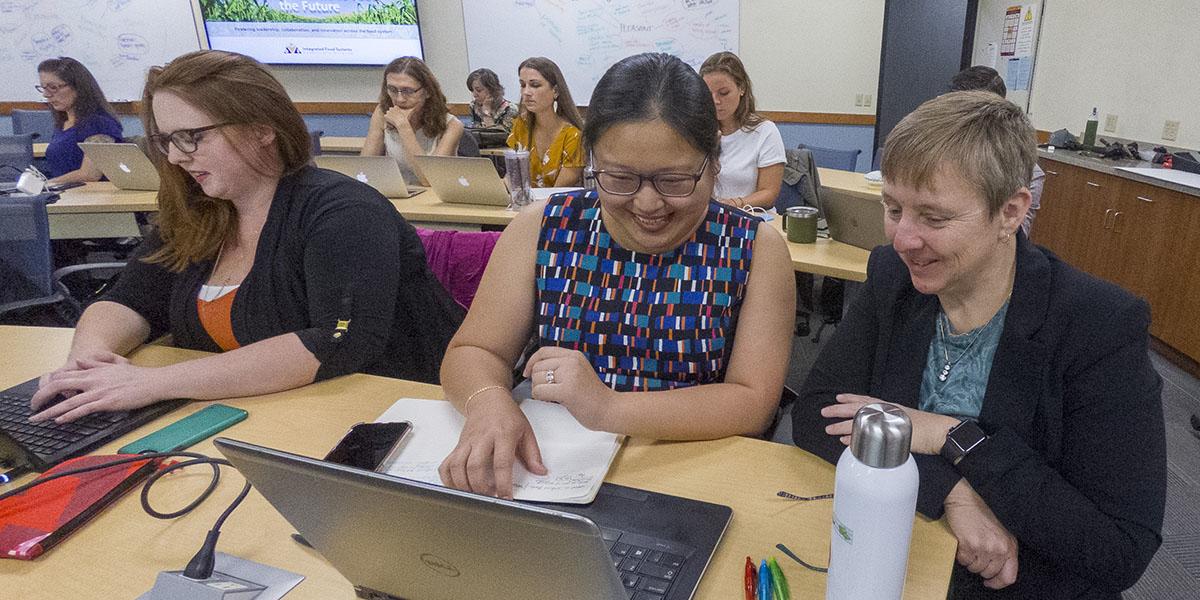

Jennifer van de Ligt, PhD, spent more than 15 years working with the food industry—where she held numerous leadership positions at global food companies—before joining the University of Minnesota as director of the Integrated Food Systems Leadership program (IFSL) in the College of Veterinary Medicine. This experience made her uniquely suited to align academic research on food issues with real-world applications.

“What I learned in those years is that academia does an incredible job training people to be subject matter experts. But when you get out into the workforce, you’re asked to do so much that’s outside your expertise,” says van de Ligt, who recalls her own experience navigating the most effective ways to communicate with shareholders.

I realized that if I explained the science using a business context, the business leaders would grasp why the science mattered to them and innovation happened a lot more efficiently.

Jennifer van de Ligt, PhD

“I was a scientist talking to business professionals,” she says. “I realized that if I explained the science using a business context, the business leaders would grasp why the science mattered to them and innovation happened a lot more efficiently.”

The IFSL certificate program is specifically designed for working professionals with two to 10 years of food system experience looking to advance their career through understanding the interconnected nature of the food system, evaluating how their work impacts the system, and improving leadership skills within the food system context.

“Our target audience is anyone affiliated in any way with the food system,” says van de Ligt. The current cohort includes students in fields that range from marketing specialists and product developers to construction professionals who build food manufacturing plants. “We’d love to have professionals from the animal production and animal health care sectors in the program.”

In addition to her work with IFSL, van de Ligt directs the Food Protection and Defense Institute (FPDI), which works to create resilient supply chains that are protected against those who aim to cause harm through manipulating the food system. The institute also delves into risk assessment for disease transmission through food sources.

In this respect, van de Ligt brought her expertise to the multi-disciplinary U of M African Swine Fever (ASF) response team. The ASF virus has swept through China since summer 2018. In that time, China has lost over half of its pork supply and ASF is now affecting pigs throughout Asia. The response team brought together feed manufacturers, veterinarians, and pork producers to facilitate conversations between all aspects of the supply chain so they could better understand the risk of ASF entering the United States through the feed supply. Because of significant restrictions on testing with ASF virus, the team is currently developing a test that can predict the behavior of ASF virus through using a surrogate virus. The specific surrogate virus the scientists are using is better than most other options, which will help speed the evaluation of mitigation strategies.

Without healthy, productive animals we simply cannot feed the world.

Jennifer van de Ligt, PhD

Food security is the concept that ties all of van de Ligt's roles together. “Animal health is critical to food security because so much of the protein that is consumed on a global basis is of animal origin,” says van de Ligt. “Without healthy, productive animals we simply cannot feed the world.”