A veterinary trifecta

Three generations of the Laurence family earn their DVM degrees from CVM

Three generations of the Laurence family earn their DVM degrees from CVM

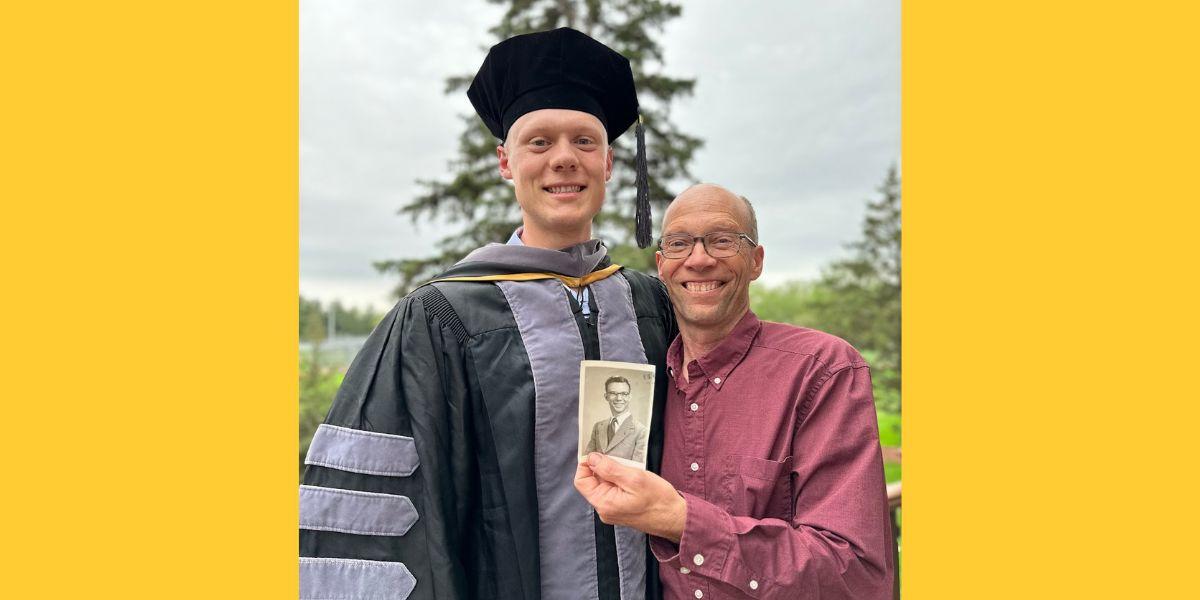

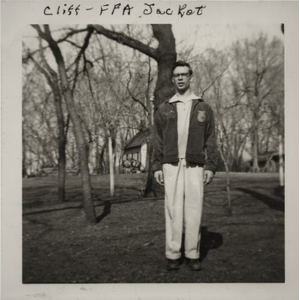

Drs. Nathan (left) and Gregg Laurence pose with a photo of Cliff Laurence following the College of Veterinary Medicine Commencement Ceremony on May 13, 2023.

At the start of World War II, Dr. Cliff Laurence was a young boy in California’s Bay Area. The West Coast had been designated a theater of operations because of ongoing military actions and the threat of attack during the war. To shelter Cliff and his two siblings, his mother sent them to their grandparents’ farm in southern Minnesota.

On the farm, Cliff enjoyed helping care for the dairy cows, horses, sheep, and pigs. Perhaps that love of animals came from his grandfather who, more than once, kept watch over a sick horse in its stall, sleeping next to it until his wife called him in from the barn.

The experiences on the farm and living down the road from a local veterinarian named Dr. Dahl inspired Cliff to pursue veterinary medicine as a career—an inspiration that it turned out, would run in his family. When he graduated from the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) in 1961, Cliff became the first of three generations of Laurence men to obtain a veterinary degree at the University of Minnesota (U of M).

Upon graduating from New Ulm High School in 1954, Cliff left the farm and ventured to the city to attend the U of M. Although a dedicated student and hard worker, Cliff managed to have fun during his time at the CVM. His classmate, Neil Anderson, described one occasion in April of ‘59 when Cliff led a carload of classmates up to Lake Superior for a late-night smelting trip.

“Not to fear,” Anderson joked, “he had them back in class at 8 a.m. the following morning, a travel-weary bunch but cheerful.”

At the time that Cliff attended the CVM, tuition costs as a Minnesota resident hovered around $100 per quarter. There was just one female student in the Class of 1943. With new graduates likely to make less than $10,000 a year, Cliff was fortunate to have graduated debt-free.

Upon graduation, Cliff joined a practice in Clara City, Minn., where he focused on large animal medicine but had a growing interest in small animal care. Eventually, Cliff partnered with another pioneering alumnus of CVM, Vern Olson. Tragically, in 1968, just seven years after obtaining his DVM degree, Cliff passed away because of complications following a surgery.

Cliff left behind a young son, Gregg. His legacy for his son included his love of animals and penchant for veterinary medicine. While Gregg didn’t get a lot of time to make memories with his dad, he recalls accompanying him to work.

“I remember going on some (veterinary) calls with him,” Greg explains, adding, “I also remember when he spayed our lab, Blitz.”

While very proud of his dad’s work as a veterinarian, Gregg never felt pressure to follow in his footsteps. At a very early age, he liked the idea of becoming a veterinarian and knew that working with animals was something he could do well and also would enjoy.

Gregg’s interest in veterinary medicine also was nurtured by a series of James Herriot books. The first of the series of eight books by Herriot, “All Creatures Great and Small,” was published in the U.S. in 1972. The autobiographical stories about a countryside veterinarian in North England, the animals he treats, and their owners captivated young Gregg—further solidifying his vision of becoming a veterinarian.

When Gregg graduated from high school, he enrolled in a pre-veterinary program at the U of M–Morris campus prior to completing his DVM degree at CVM in ‘87. By that time, things at the College had changed a bit from when his dad attended. Tuition had climbed to $1,500 per quarter and the class was becoming more diverse. Close to half of the Class of ‘85 were women.

Veterinary medicine also evolved considerably from Cliff’s practice. When asked about these differences, Gregg points toward the increasing use of technology.

“Ultrasound for pregnancy diagnosis, advanced computer applications, and automation to manage the animals on very large farms, for example,” have significantly changed the way we practice, Gregg explains.

Upon graduation, Gregg left the city to practice in rural Willmar, Minn. His starting salary at the South 71 Veterinary Clinic was just over $20,000. To this day, he belongs to the practice and treats large and small animals, spending a considerable amount of time visiting farms and keeping agricultural animals healthy.

A busy veterinary practitioner, Gregg, and his wife, Karen, also had three kids in the mix. Juggling kids and work sometimes meant that one of the kids accompanied Gregg to an off-hours clinic call or a visit to a local barn. One of the Laurence kids, Nathan, especially relished the opportunity to help his dad at work.

When asked about days on the job with his dad, Nathan says two memories stood out. He recalled being quite young and spending days at a large dairy farm with 900 animals. While Gregg worked, Nathan helped the farmer's son move cows and shovel manure. He also fondly described holding puppies at the clinic as his dad helped deliver a litter via an emergency C-section. When there was a lull in the action, he built forts using empty dog food boxes.

Not surprisingly, the Laurence veterinary medicine dynasty carries from Cliff to Gregg to Nathan. At the age of 5, in his kindergarten profile, when asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, Nathan responded, “A veterinarian.” A couple of years into high school, Nathan again declared his intention to become a veterinarian and follow in the footsteps of his dad and grandfather.

At that time, according to Gregg, people were more pessimistic about the veterinary profession, citing low starting wages combined with graduates’ heavy debt loads. Knowing the long workdays required, Gregg gulped upon hearing his son’s plans but quickly resolved to help Nathan the best he could. Gregg hoped that the times Nathan had accompanied him to work had provided many glimpses of a day in the life of a veterinarian and that nothing should come as a big surprise.

Following high school graduation, Nathan completed VetFAST, a three-year program at the U of M, Morris. VetFast shaved off one year of Nathan’s undergraduate tuition expenses and provided a scholarship to further reduce costs. Like his dad and grandfather before him, Nathan then headed to St. Paul to attend CVM.

By the time Nathan enrolled at CVM, things looked much different from his father and grandfather’s graduating classes. The demand for veterinarians had grown and the class size had jumped to more than 100 students. In Nathan’s class, 12 of the students were male. The cost of delivering veterinary education had grown dramatically and, tuition rates grew in proportion. As a Minnesota resident, Nathan’s first two years of veterinary school cost over $30,000 per year. Nathan estimated that the average salary for his classmates the first year out of school ranged from $80,000 to $100,000.

In addition to changes in tuition, class profile, and salary, Nathan also noted dramatic shifts in the practice of veterinary medicine itself. Employed as a veterinarian by Northern Valley Livestock Service in production medicine, Nathan cares for large herds of dairy cows. Using new technology and computer data, he can quickly measure milk output or see disease trends in a herd by monitoring whether the level of a certain bacteria or virus found in the barn has risen to a concerning threshold.

A look at three generations of Laurence men and their stories about getting a doctorate degree in veterinary medicine illustrates changes in veterinary education and practice across the decades. At the same time, it reveals a common theme—a love of animals and an inclination to care for them and improve their health. Making their childhood dreams a reality took a lot of grit and determination.

In May 2023, when Nathan Laurence donned his regalia and walked across the stage to receive his DVM degree, his dad, Gregg, was on hand to celebrate the accomplishment. Watching with pride as Nathan received his diploma, Gregg could only imagine the joy his own father would have experienced had he been alive to see him graduate from vet school with the class of ‘87.

Given the shortage of rural veterinarians in the state of Minnesota, the fact that all three Laurence men practiced agricultural medicine is particularly remarkable. Motivated by an early interest in caring for animals, when the three generations fulfilled their dream of becoming a veterinarian, they helped to fill the needs of Minnesota farmers and their animals.