Training to serve

Assistance dog training organization, Helping Paws, celebrates 35 years and its roots in CVM research initiatives

Assistance dog training organization, Helping Paws, celebrates 35 years and its roots in CVM research initiatives

A Helping Paws assistance dog lies in the grass.

Jenny Peterson’s first service dog, a golden retriever named Alpha, holds a special place in her heart.

Living with quadriplegia, Peterson uses a wheelchair for mobility and has limited use of her arms and wrists—the result of a broken neck sustained in a downhill skiing accident at age 17. In the late 1980s, a few years after her accident, a new research program at the University of Minnesota exploring the potential of dogs assisting people with disabilities introduced her to Alpha. The pairing changed everything.

“In those early years after the accident, I was really trying to figure out who I was and Alpha helped save my life in small ways every day,” she recalls. “He got me out and much more social. I became more secure in both being a person with a disability and being vulnerable out in the world and at home.”

Alpha was special in another way. More than three decades ago, he and Peterson were the first graduate team of the research program, which transformed into Helping Paws, an organization that seeks to further people’s independence and quality of life through the use of assistance dogs. Helping Paws is celebrating its 35th anniversary this year and placing more than 300 dogs with clients—an impact made possible through the UMN collaboration decades ago.

Helping Paws started as a pilot project by the Center to Study Human-Animal Relationships and Environments (CENSHARE). CENSHARE was established in 1981 by the Office of the Academic Vice President, the dean of the School of Public Health, and the dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM).

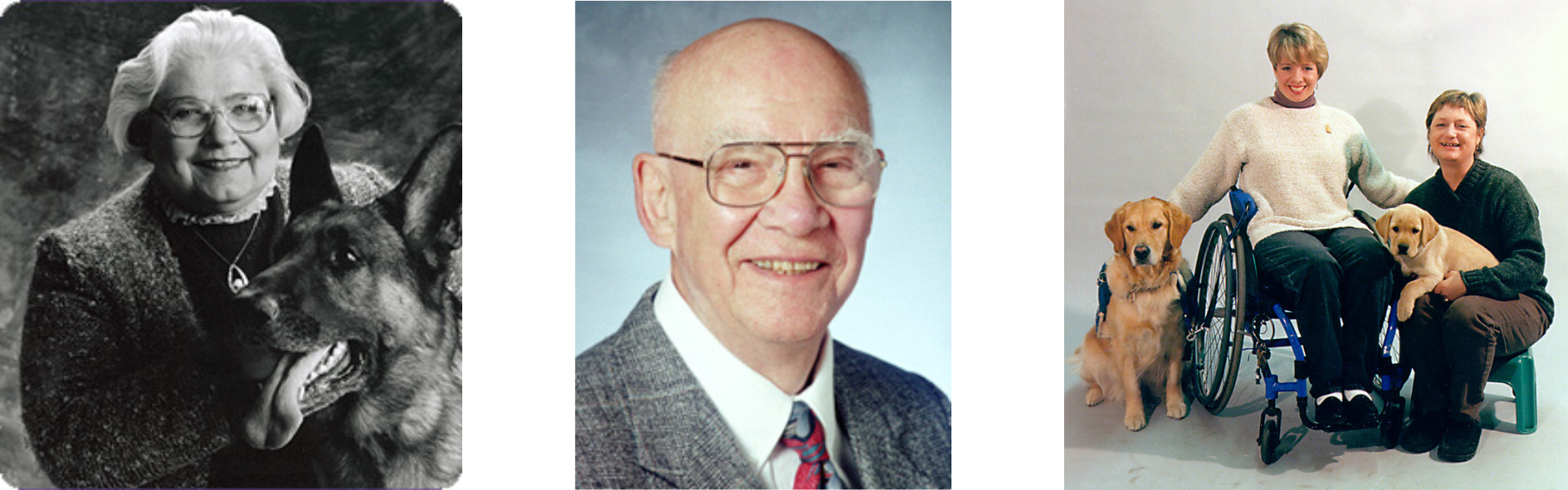

Co-founded and led by CVM and SPH professor Robert K. Anderson and obedience training expert Ruth Foster, the center primarily focused on helping people understand pet behavior problems and working with local therapy and service animal organizations throughout the 1980s and 1990s. CENSHARE also has provided education and research on the human-animal bond.

A 1985 pilot project that gave rise to Helping Paws was part of these efforts. At the time, training guide dogs to assist people with vision impairments was an established practice, but the pilot sought to take dogs beyond that role.

“This was the next step of having dogs work with people with physical disabilities,” says Alyssa Golob, executive director of Helping Paws.

The program saw success and became an independent nonprofit in 1988 under the direction of Co-Founder Eileen Bohn, with Alpha and Peterson graduating that same year. In the decades since, it has placed trained assistance dogs with veterans and people with disabilities, and in facilities such as schools, hospitals, and courthouses. As part of its growth over the past 35 years, Helping Paws now has its own breeding program, a network of dedicated volunteer foster training homes, and many people whose lives have been positively affected by an assistance dog.

In Peterson’s daily life, her dog—currently a recent successor dog named Emerson who took over for her now-retired predecessor, Aster—helps her complete physical tasks but also has a greater impact. When out in public, the presence of her service dog has helped facilitate conversations that extend beyond small talk about topics like the weather.

“It’s much more meaningful,” Petersons says. “Even some of those simple interactions can be deeper and just a different level of connection.”

It’s a positive outcome Golob says others with assistance dogs have experienced as well. In fact, studies have found people with disabilities assisted by service dogs have significantly better psychosocial health and reported positive impacts on mental, emotional, and social well-being than peers without dogs. Members of the public interacting with service dogs and their handlers also see a benefit.

“The dog becomes a bridge and it makes it easier for people to have a conversation with someone in a wheelchair,” Golob says. “Now, that person is learning about disabilities and learning to build their own tolerance around people that are different and look different than them.”

Though Alpha has long since passed, four successor service dogs have followed in his footsteps, each fulfilling an important job while bringing joy and meaning to Peterson’s life in their own way.

“Having had a service dog for all these years—I can't imagine life without one,” she says.