CVM celebrates female pioneers

Celebrating the trailblazers and advocates that made a way forward for women in the field of veterinary medicine.

Celebrating the trailblazers and advocates that made a way forward for women in the field of veterinary medicine.

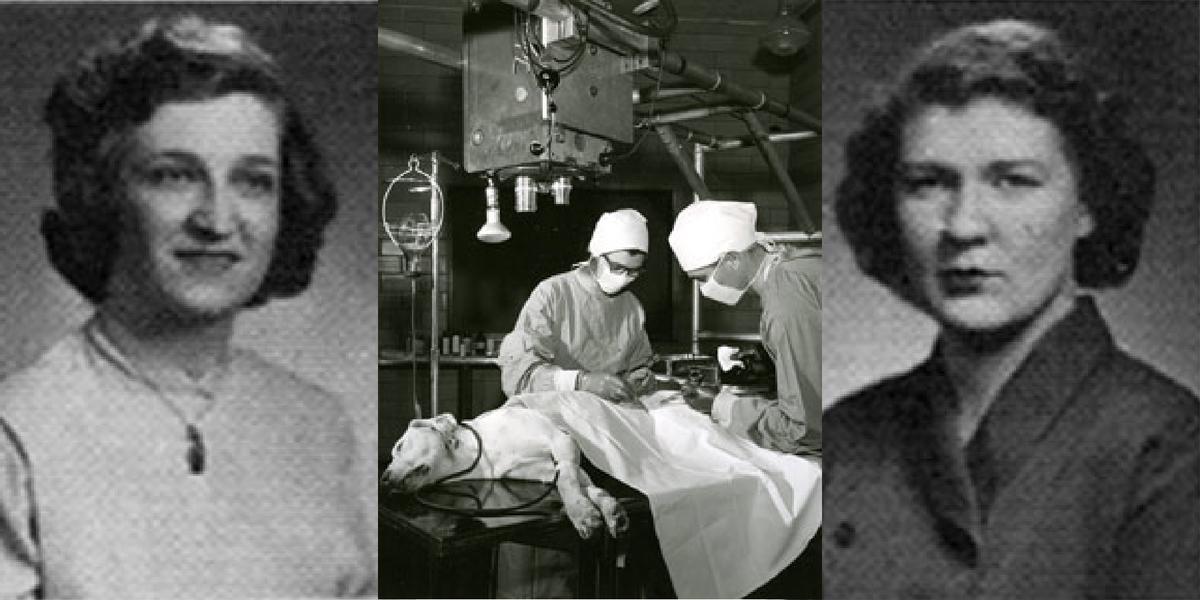

JoAnne Schmidt O’Brien, DVM, and Bee Hanlon, MS, DVM, DACVIM, the College of Veterinary Medicine’s first female veterinary students, opened the door for women to pursue studies in veterinary medicine at the University of Minnesota. Throughout their careers, both women continued to break new ground in the veterinary industry, achieving practice ownership, board certification, and research and teaching milestones. Dr. Schmidt and Dr. Hanlon solidified their commitment to a legacy of leadership through estate gifts that continue to foster leaders in our community today.

Leaders such as Eva Furrow, VMD, PhD, DACVIM, an associate professor of Small Animal Internal Medicine and Genetics, demonstrate the lasting impact that Bee and JoAnne made in their field. Dr. Furrow was the 2010-2011 recipient of the Hanlon/Schmidt Fellowship award, and now mentors other graduate students in her work at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

I challenge anyone to read the stories of these two remarkable pioneering women and not feel a deep sense of admiration for what they achieved.

Sandra Godden, DVM, DVSc

Sandra Godden, DVM, DVSc, leads as interim dean of graduate studies and a professor in the Department of Veterinary Population Medicine. Godden shares: “I challenge anyone to read the stories of these two remarkable pioneering women and not feel a deep sense of admiration for what they achieved. Their determination and success has served to inspire generations of women entering the field of veterinary medicine and veterinary research. We are indebted to them for the legacy that they created.”

In honor of Bee, JoAnne, and all the mentors that help clear the path for our successes, we ask you to give today to support the next generation of leaders in veterinary medicine. Make a gift to the Dr. Bee Hanlon and Dr. JoAnne Schmidt O’Brien Graduate Fellowship Fund, or contact Bill Venne at: venne025@umn.edu or 612-625-8480 to learn more about how you can help.

I can’t help but smile when I think of the power of determined women

Bee Hanlon reflecting on JoAnn Schmidt O’Brien’s fight for admission to the College of Veterinary Medicine

Birth name: Griselda Frances Gutcheck

Born: January 25, 1922, in Anaconda, Mont.

Died: January 14, 2010, in Roseville, Minn.

Hanlon graduated from the Anaconda High School in 1939. She attended Montana State College where she majored in entomology and graduated in 1943. In a 2008 interview, Hanlon explained:

“I wanted a career that would involve the outdoors. The ‘bug’ world always fascinated me, and I wanted to know more about their world, their beneficial and harmful effects. I was especially interested in the medical aspects in the carriers.”

Following college, Hanlon worked at the Hooper Foundation, which is affiliated with the University of California Medical School in San Francisco. There, she worked on an epidemiology team in a field unit, studying equine encephalitis and its potential transmission to humans.

In 1944, Hanlon joined the U.S. Navy as a Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). She later served for a year and a half on an epidemiology team in San Diego. After finishing her time in the Navy, Hanlon remained in San Diego to serve as a medical technician studying tuberculosis.

While in the service, part of Hanlon’s duties were that of a page. She recalled one day she made a delivery to the Balboa Park Zoo in San Diego. While there, Hanlon met the head of the zoo’s animal hospital and witnessed her performing a necropsy on a gorilla.

“It was through my contact with her that I became interested in the diseases of animals,” Hanlon recalled in 1987. Her career decision also was guided by having grown up on a small hobby farm.

Hanlon and her husband moved to Minnesota (his home state) so he could apply to medical school. At the same time she considered applying to the College of Veterinary Medicine, which had been open for about a year. She worked part time as a typist in the Rural Sociology Department while taking required livestock courses to make her eligible for admission to veterinary school. Hanlon completed those courses and applied for the college’s second class in 1948 and was accepted—but not without a few bumps. Initially, she and the only other female applicant, JoAnne Schmidt O’Brien, were rejected. Hanlon had returned to Montana for the summer, with plans to head back to Minnesota come fall.

“And it was just, I believe, a week or a weekend before school opened, and I received a telegram stating they changed their minds,” Hanlon said in 1987. “They were allowing two women into the school. And if I wanted to attend, I should get there on the first day, which I did.”

Upon her arrival, Hanlon learned that Schmidt O’Brien’s summer employers took up a campaign to get the two women admitted, flooding university leaders’ offices with letters protesting the initial rejection. The veterinary school dean relented and added two places for the women.

When asked how professors treated her and Schmidt O’Brien, Hanlon noted they were kind but kept their distance. “They thought we were screwballs, I guess, getting in with the men,” she said. “We weren’t foolish, we wanted to get through. I don’t recall as far as my classmates were concerned, I think a lot of them just wanted to laugh, they wondered what we were doing there.”

Hanlon’s role as a pioneering woman didn’t stop after school. Hanlon accepted a research fellowship with the University while pursuing a master’s degree. In 1955, she became the first board-certified female veterinary radiologist in the American College of Veterinary Radiology (ACVR).

Hanlon became the first woman veterinarian on the faculty at the University, and the only one for a number of years—eventually making full professor in 1973. In all, Hanlon’s teaching career spanned 33 years at the University. She retired in 1985, having trained hundreds of veterinary students. In 2009, the University of Minnesota held a ceremony to recognize Dr. Hanlon and other female scientists just shortly before her death.

On why more women started applying to veterinary school during her time as a faculty member:

“[Women] think if they want to get some somewhere, they have to be that much better than men to qualify….This is the innermost feeling. I’ve got to show that I could do better. And I know that JoAnne and I tried our best because we wanted to keep that door open for women.”

Reflecting on her career:

“It’s been really an experience, and I think back, and you’ve asked me if I’d do it over again—I certainly would have. I don’t know what else I would do.”

Hanlon adopted the name “Bee” because her childhood friends couldn’t pronounce Griselda. Her family referred to her as “Baby” which morphed into “BB” and eventually Bee.

Birth name: JoAnne Schmidt

Born: 1928 in the Chicago area

Died: April 21, 2008, in Washington, D.C.

Per an interview with Bee Hanlon: “[O’Brien] had most of her pre-veterinary courses in Illinois prior to making [an] application in Minnesota. She also had to establish residency and was able to do so by applying as an emancipated minor because it was necessary for her to work while going to school. She was [one] of the youngest members in the class, and I was among the older group.”

Admission to veterinary school came for O’Brien after a string of obstacles threatened to keep her from pursuing her education. Initially, she and the only other female applicant, Bee Hanlon, were rejected. O’Brien then spent the summer working for a dog kennel, one of the owners of which was a University alumna. Upon hearing about O’Brien’s rejection, her employer mounted a letter-writing campaign among her fellow women alumni that tipped the balance and allowed O’Brien and Hanlon to enter school. Two seats were added to accommodate the women, bringing the class size to 50 people.

After graduating in 1952, O’Brien went into small animal practice. She was one of the first women to own and run her own animal hospital, according to Hanlon. O’Brien married and moved to Washington D.C. in 1958. In addition to her practice, O’Brien was interested in theriogenology and supported research on the topic conducted at area veterinary schools. As a veterinarian and as an animal breeder, O’Brien had long been intrigued specifically by the role hypothyroidism plays in canine reproduction. While thyroid levels in an animal might be within normal ranges, O'Brien speculated that levels on the lower side of the “normal” ranges might be insufficient to promote maximum fertility.

Schmidt O’Brien often worked long hours on top of school to pay for her tuition. She’d nod off in class so she asked Hanlon to nudge her awake when need be.

In addition to her veterinary practice, O’Brien also was a champion breeder of Chow Chows, operating Linn Chow Kennel. She continued the legacy of her parents, who also bred champion Chows. Upon arriving in Washington D.C., she met Dr. Imogene Earle of Pandee Chows. They began a 20-year partnership that resulted in at least 33 champions, numerous national and regional specialty wins. O’Brien was active in showing and judging up until her death. Learn more about her breeding career here.