- Issue:Tags:

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) has spread across the central United States over the past 50 years and is currently found in 26 states. It’s also found in Canada, several Scandinavian countries, and parts of Asia. The transmissible neurological disease produces small lesions in an animal’s brain and often results in abnormal behavior, weight loss, loss of bodily functions, and death. CWD affects white-tailed deer, mule deer, red deer, sika deer, caribou, reindeer, elk, and moose. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against eating meat from CWD-infected animals. University of Minnesota researchers have been collaborating to stop CWD in its tracks.

A widespread, tenacious disease

CWD is spread by misfolded prion proteins. Normal prion proteins help to metabolize copper and zinc. When they misfold, their structure changes and that can cause several fatal neurodegenerative diseases in humans and animals. CWD-causing prions are not alive and can only be destroyed with specialized equipment, which is what makes CWD so difficult to mitigate.

CWD prions can persist in the environment for years—they can bind to soil and plants can absorb them through their root system. A CWD-infected deer has the potential to spread many prions into the environment, which can infect other deer. Monitoring and predicting the spread of CWD in the wild is incredibly complex and, according to Peter Larsen, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences (VBS), tracking the CWD prion protein in the wild would be similar to modeling the ecological spread of radioactive material.

Infected animals can live for at least 16 months before dying, and their blood, tissues, and fecal material can remain a source of new infections for years after death. When an animal dies of CWD, the carcass is also a source for new infections. The misfolded prion underlying CWD is closely related to the prion that causes mad cow disease and scrapie. Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, ALS, and Parkinson’s in humans are similar to prion diseases in that misfolded proteins underlie each disease.

CWD, which has spread in both wild and farmed deer populations, can spread directly among affected animals. It may also spread indirectly, remaining for years in plants and soil that have been exposed to it. Scientists are concerned that this disease could cross species or even be zoonotic, meaning exposed humans could be at risk of contracting it.

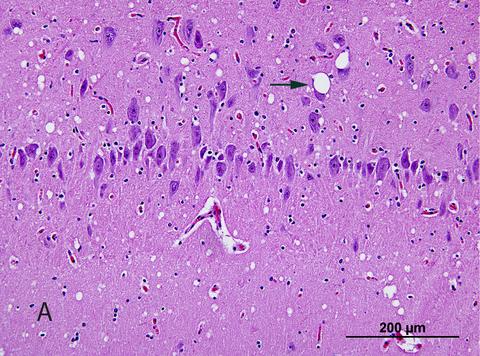

“I have watched CWD move into Minnesota and I’m frustrated that we haven’t found strategies to slow down or contain the disease,” says Jeremy Schefers, DVM, PhD. Schefers is a pathologist with the Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (VDL) and has spent over 10 years looking at thousands of tissue samples to confirm the presence of CWD. “Unfortunately, our lack of a rapid test that works on live animals, or our ability to test other things, such as soil, meat processing equipment, and samples from other animals that might carry the prion, clouds our understanding of CWD transmission.”

A rapid and reliable field-based test would help answer numerous CWD-related questions. How long does an infected animal shed the CWD prions that can infect other animals? Exactly how long do the prions survive in the environment? What techniques inactivate the CWD prions, either in animals or in the environment?

Too little, too late

Current CWD testing is time-consuming and expensive; it also requires killing the animal. It can take up to 14 days and necessitates further testing to confirm results. At present, wildlife managers can only learn where CWD has been, not where it is circulating, which makes controlling it challenging. The need for real-time data and more efficient testing that is accessible to everyone is growing more prevalent as the disease continues to spread.

“Our current tests limit those tasked with managing CWD by requiring euthanizing deer without knowing their infection status,” says Larsen. “We must provide stakeholders with new diagnostic technologies that provide a real-time view of the CWD landscape. These new diagnostic tools will provide CWD managers with a suite of new options for monitoring and mitigating the disease.” Larsen is co-leading a research team at the U of M. He is a genomicist and bioinformatician with expertise in infectious disease, neurodegenerative disease, and the application of nanotechnology for molecular diagnostics. The project's co-leader, Pamela Skinner, PhD, professor in both VBS and the Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology PhD Graduate Program, is a prion disease researcher.

New solutions from the U

In January, Larsen; Skinner; Davis Seelig, DVM, PhD, DACVP, assistant professor in the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences; Trevor Ames, DVM, MS, dean of the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine; and Jerry Torrison, DVM, PhD, DACVPM, professor in the department of Veterinary Population Medicine and director of the VDL, appealed to the Minnesota House Environment and Natural Resources Policy Committee for $1.8 million to research early detection of CWD.

With this funding, researchers could develop a test that would detect the presence of CWD within minutes or hours. The test would be more efficient, easier to use, and could rapidly screen live animals or environmental samples for CWD—not just deceased animals. This approach would not only result in a faster, more effective test but also make the testing accessible to more labs.

The team’s novel approach to CWD testing would test deer at an early stage in the disease process, which could help reduce spreading. The researchers are hopeful that, with funding, they can create a working prototype in two years.

"The test we envision would ultimately be field deployable and could be used in a variety of conditions,” Larsen says. “It would allow for better surveillance, enabling state agencies to respond quickly and effectively to both manage and potentially eradicate the disease. We have the expertise and the necessary biocontainment facilities to safely handle the CWD prions. We have identified several promising avenues for diagnostic development that focus on microfluidics and nanotechnology and are ready to begin testing immediately. Any endeavor of this magnitude is a challenge, but we are confident of our future success.”

Photos Courtesy of Marc Schwabenlander