Searching the unseen

Researchers seek to understand role of the urinary microbiome in formation of uroliths

Researchers seek to understand role of the urinary microbiome in formation of uroliths

Riley, a shih tzu whose health was negatively impacted by urinary stones.

After becoming a veterinarian, one of the first patients Dr. Emily Coffey treated was a dog named Riley. Riley’s owners brought him to the clinic after spotting blood in his urine and noticing he was straining to urinate. An X-ray soon revealed a large stone sitting in Riley’s bladder.

The sharp, jagged stone irritating Riley’s bladder explained his bloody urine and incredible discomfort. Analysis of the stone revealed that it consisted of calcium oxalate, the second most common type of urinary stone in dogs. In addition to being painful, calcium oxalate stones require invasive treatments.

Stones typically occur in dogs between 5–12 years of age and are more common in males. Certain breeds including miniature schnauzers, Lhasa apsos, Yorkshire terriers, miniature poodles, shih tzus, and bichon frises experience stones more frequently. Veterinarians are seeing increasing rates of urinary and bladder stones in general and, once a dog gets a stone, it is likely to develop others. In Riley’s case, this was already the fourth time he had to undergo stone removal.

Diagnosis and treatment options vary depending on the location and type of stone. Treatments may include a procedure called lithotripsy to break up the stone, surgical removal, placing the dog on a special diet, or, best case scenario, waiting and watching. Veterinary bills typically range from several hundred to a couple of thousand dollars for each stone occurrence—a big expense for pet owners with dogs prone to forming stones.

The desperate need for strategies to prevent kidney and bladder stones requires a better understanding of why they form in the first place. Researchers have studied why some dogs are more susceptible to developing recurrent stones and what causes different types of stones, but many questions remain. Coffey and her mentor, Dr. Eva Furrow, an associate professor of internal Medicine at the College of Veterinary Medicine and co-director of the Minnesota Urolith Center, set out to learn more about the cause of stones.

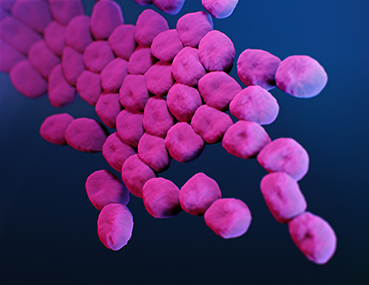

Their search has a unique focus, the urinary microbiome. Contrary to popular belief, urine is not sterile—even in healthy individuals. Urine houses rich ecosystems of microorganisms like bacteria that play important roles in keeping the urinary system healthy. Known as the urinary microbiome, these communities have recently been considered a contributing factor in the formation of calcium oxalate stones.

“Disturbances in the microbiome are linked to several urinary disorders,” Coffey says. “We have reason to believe the microbiome may be important in urinary stone formation, too.”

Dogs are one of the few species, aside from humans, that form these stones naturally—making them very helpful for studying this disease. Yet relatively little is known about the microbiome in dogs with stones. Coffey and Furrow’s research seeks to uncover potential relationships between the urinary microbiome and calcium oxalate stone formation in dogs.

Occasionally considered a “supporting organ,” the microbiome refers to thousands of species of microbes that populate the body. These microbes or “bugs” include bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses that maintain the health and stability of many organs and systems in the body but are also known to contribute to disease.

Present at birth, the microbiome constantly evolves during our lifetime and is affected by a host of factors including the environment, diet, other illnesses, the use of antibiotics, and more. Changes in the microbiome are known to contribute to many diseases ranging from urinary tract infections, obesity and heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and stone formation. Coffey’s research on the role of the microbiome in stone formation is part of the growing body of work expanding the understanding of the interplay of microbes and disease.

“It’s an exciting new field of research with tremendous potential to improve urinary system health,” Coffey says.

So far, they've identified several bacteria that significantly differ in abundance between the urine in the dogs with and without stones. One of these bacteria, Acinetobacter, is also associated with human stone formation. The discovery of specific bacteria of interest is an important step in solving puzzling questions about stone formation. Ultimately, a better understanding of how the microbiome contributes to stone formation will lead to prevention and treatment strategies — helping dogs like Riley return to happily chasing tennis balls.

Because of the similarities in stone formation in humans and dogs, what we learn about the disease in dogs helps humans who are suffering from this disease as well. The Minnesota Urolith Center at the University of Minnesota is a leader in providing stone analysis, developing treatment recommendations, and researching stone formation in dogs and cats. It serves approximately 45,000 clinics in more than 100 countries around the world. The lab has analyzed stones from more than 1.5 million patients.

Working on several projects to expand upon their initial findings, Coffey and Furrow are currently recruiting dogs for a larger study looking at both the gut and urinary microbiomes in dogs with stones. The study will explore how these bacterial communities affect specific features in the urine. With an eye toward improved prevention and treatment options, Coffey described plans for a future study to “evaluate if, and how, specific nutrient supplements can be used to manipulate the microbiome and stone risk.”

Research conducted by the Minnesoa Urolith Center is advancing veterinary medicine by improving the diagnosis, removal, and prevention of urolithiasis using minimally invasive methods. Please contact Senior Development Officer Mindy Means at mkmeans@umn.edu or 208-310-3562 if you are interested in supporting this research. You also can give to the Minnesota Urolith Center using this online form.