Opening the door

First female CVM students broke down barriers and paved the way for generations of veterinary leaders

First female CVM students broke down barriers and paved the way for generations of veterinary leaders

When the door to veterinary school shut in their faces in 1948, Griselda “Bee” Hanlon and JoAnne Schmidt O’Brien found themselves at a crossroads.

The pair were the only female applicants to the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine’s second class of students but were not among the 48 men admitted to the school. For the moment, their veterinary dreams came to a standstill.

While Hanlon headed off to Montana for the summer, Schmidt O’Brien spent the season working for a dog kennel. It just so happened that one of the owners was a University alumna. Upon hearing about Schmidt O’Brien’s rejection, her employer mounted a letter-writing campaign among her fellow alumnae that tipped the balance. CVM’s dean relented and two seats were added to accommodate the women, bringing the class size to 50 people.

“I can’t help but smile when I think of the power of determined women,” Hanlon said in a 2008 interview, reflecting on Schmidt O’Brien’s fight for admission.

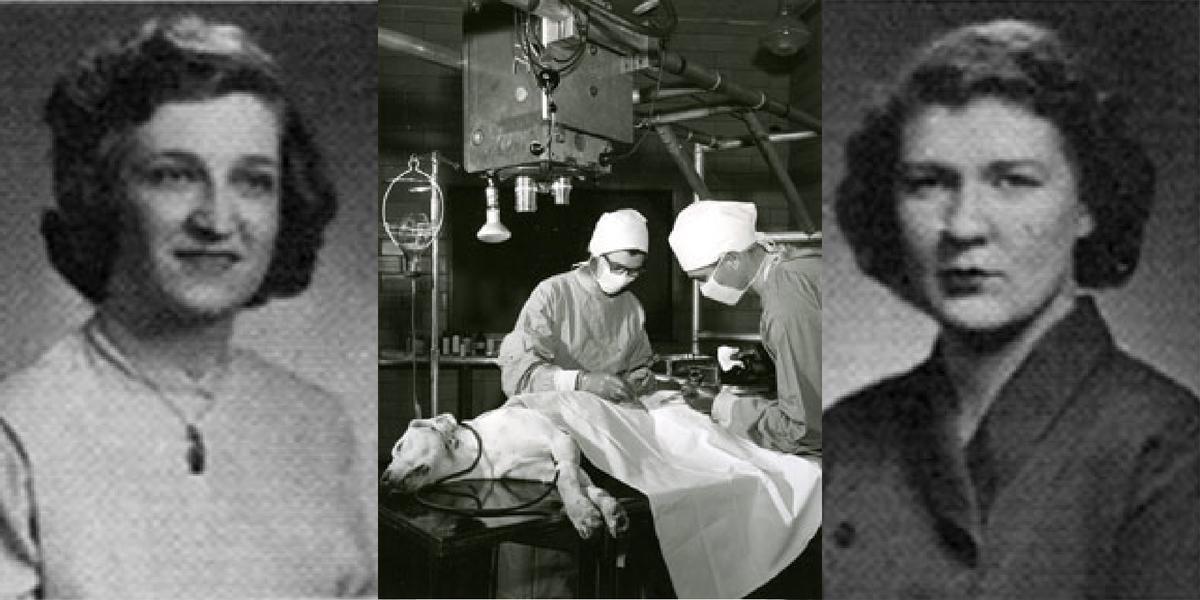

By boldly stepping into a place no women had gone before, together Hanlon and Schmidt O’Brien became the first female veterinary students in Minnesota, successfully completing their studies among the second graduating class of the CVM and helping to transform their profession for generations of women to follow.

Neither Hanlon or Schmidt O’Brien’s role as a pioneer stopped after school. Upon graduating, Hanlon accepted a research fellowship with the University while pursuing a master’s degree. In 1955, she became the first board-certified female veterinary radiologist in the American College of Veterinary Radiology (ACVR) and in the state of Minnesota.

Hanlon became the first woman veterinarian on the faculty at the University and the only one for a number of years. She worked her way up through the ranks, starting as an instructor and eventually made full professor in 1973. In all, Hanlon’s teaching career spanned 33 years at the University. She retired in 1985 and passed away in 2010.

While Hanlon made her mark in academia, Schmidt O’Brien set off to the Chicago area where she worked with small animals. In the mid-1960s, she moved to Washington D.C. to work at the W.P. Collins Memorial Hospital. In 1969, she bought the hospital—becoming one of the first women ever to own a private veterinary practice.

In addition to her practice, Schmidt O’Brien also gained recognition as a breeder of champion Chow Chows. A 20-year professional partnership with fellow female veterinarian Imogene Earle, DVM, PhD, resulted in at least 33 champions, numerous national and regional specialty wins, and an all-breed Best In Show.

Schmidt O'Brien also served on the Board of Veterinary Medicine for the District of Columbia and on the admissions committee for the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech, where she was involved with the creation and funding of a laboratory for companion animal reproduction and endocrinology studies.

As a veterinarian and breeder, Schmidt O’Brien was interested in theriogenology—the branch of veterinary medicine encompassing all aspects of reproduction—and supported research on the topic with financial gifts to veterinary schools in the Maryland-Virginia area.

Today, Hanlon and Schmidt O’Brien’s legacy lives on and continues to foster leaders in the veterinary medicine field. In their honor, the CVM created the Dr. Bee Hanlon and Dr. JoAnne Schmidt O’Brien Graduate Fellowship Fund.

Dr. Eva Furrow, an associate professor of small animal internal medicine and genetics, demonstrates the lasting impact that these two women have made. Furrow was the 2010-2011 recipient of the Hanlon/Schmidt OBrien Fellowship award, and now mentors other graduate students in her work at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

“The Hanlon/Schmidt O’Brien Fellowship award provided me with protected time to immerse myself in research during my residency program,” Furrow says. “My passion for research grew and launched an academic career in veterinary medicine and translational research. As faculty, I further felt the support and impact of the fellowship when one of my graduate students became an awardee.”

Since Hanlon and Schmidt O’Brien’s time in school, the demographics of the veterinary field have shifted dramatically. In 1970, the national average for veterinary medical college male enrollment was 89 percent. Now, women represent more than 80 percent of enrolled vet students.

At CVM, the tide shifted in the late 1980s with women representing the majority of enrolled students. Similar to national trends, the percentage of enrolled students identifying as women has climbed to 80 percent.

The trend continues after graduation. The American Veterinary Medical Association found in 2019 that 63 percent of the U.S. veterinary workforce identified as female, marking a 12-percent increase in female veterinarians over the past decade.

Women also continue to forge their way upward into leadership roles, including administration positions at veterinary colleges. In 2017, 42 percent of veterinary school administrators were women, compared with only 28 percent in 2012.

Female representation among leadership positions also continues to increase at CVM, starting at the top with Dr. Laura Molgaard becoming the first female dean at CVM in 2022, following nearly two years of serving as interim dean.

Dr. Sandra Godden leads as interim dean of graduate studies and a professor in the Department of Veterinary Population Medicine and is grateful to Hanlon and Schmidt O’Brien for breaking down gender-based barriers.

“I challenge anyone to read the stories of these two remarkable pioneering women and not feel a deep sense of admiration for what they achieved,” Godden says. “Their determination and success has served to inspire generations of women entering the field of veterinary medicine and veterinary research. We are indebted to them for the legacy that they created.”

The 2022-2023 school year marks the 75th anniversary of the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine.

Join us as we revisit milestones and innovations in the College's history and look forward to our future success in advancing veterinary medicine through teaching, research, and service.