Advancing the cutting edge

Gross anatomy instruction at CVM holds a history of innovation

Gross anatomy instruction at CVM holds a history of innovation

Humans have long been interested in the anatomy of animals and how it relates to their own bodies. It’s a fascination that can be traced back through thousands of years of scientific observation and dissection.

Over the centuries, anatomical instruction has continued to evolve within the greater field of veterinary medicine and contribute to an enhanced understanding of the structure, location, and composition of animal bodies that is necessary to study, diagnose, and treat their ailments.

The curriculum at the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine wouldn’t be complete without the subject of gross anatomy, nor would the education of thousands of veterinarians who have graduated from the school since its founding in 1947.

In the decades since, the gross anatomy group has changed size and shape but its goal remains to provide the best education possible to prospective veterinarians—an education that also has transformed through the years.

Medical imaging such as CT and MRI scans are bringing anatomy to life in greater detail than ever before. Textbooks and lectures have gone digital, allowing for greater flexibility in how students approach the subject.

Many facets of the College have changed throughout its 75-year history, including its administrative structure. Though no longer present, a department of anatomy was once part of its makeup. This was common for many veterinary colleges and medical schools at the time, according to Professor Emeritus Dr. Thomas Fletcher, who came to CVM as a graduate student in 1961. He later joined the faculty and spent 52 years teaching gross anatomy courses for the College until his retirement in 2017.

“Beyond classroom teaching, the typical veterinary anatomy department in those days focused on producing textbook chapters and teaching manuals; many faculty participated in an international effort to revise anatomical terminology,” he says. “However, at CVM, there was also a research thrust and reputable graduate programs enhanced by medical school collaborations.”

During his time as a graduate student, Fletcher notes the CVM anatomy department was composed of two senior faculty members, a half dozen graduate student instructors, and several civil service technicians. The group was led by department head Dr. Ralph Kitchell, who taught courses in gross anatomy and neuroanatomy. His colleague, Dr. Al Weber, taught microanatomy and embryology and is credited with receiving a grant that procured the College’s first electron microscope—also the first of its kind to be located in a veterinary college anywhere.

Over the last several decades, factors ranging from new technology to funding changes have driven and shaped veterinary medicine education as a whole. It has been no different for the gross anatomy curriculum at CVM.

They are changes Dr. Vic Cox, professor emeritus of the Department of Veterinary Biomedical Science, saw firsthand during his more than 40-year career with the College.

“Over the last 100-plus years, there have been countless advances in medical science leading to more science and less ‘art’ in the practice of veterinary medicine,” Cox says. “Therefore, more curricular time was devoted to new scientific concepts and techniques. In order to do so, anatomy curricular time was reduced."

It’s a trend Fletcher also observed during his time at CVM. Expanding clinical knowledge and techniques, along with the economic need to limit the veterinary curriculum to just four years, resulted in reduced anatomy course offerings, which had occupied a large portion of the early veterinary medicine curriculum, he says.

This was partly because of the expanded production of anatomy textbooks, which opened up the subject matter to non-anatomists.

“In the 1950s, there was only one anatomy textbook, and instruction required knowledgeable anatomists,” Fletcher says, adding clinicians also had begun including more basic science concepts, such as anatomy, in their instruction to students.

Cox notes that in most cases, the reductions to gross anatomical courses were reasonable. For example, nerves of the bovine legs are no longer covered in class because nerve blocks—injections that prevent the reception of pain signals in nerves—and surgery on cow limbs are rarely practiced.

This refinement continues today, as instructors focus on information that students would use regularly, according to Abby Brown, an education program specialist who has been with the anatomy group since 2005. Brown leads the Teaching Technician Team, a recently formed, centralized group of veterinary technicians that support the anatomy labs, along with various other core courses with labs within the first three years of the veterinary curriculum.

“We have tried to focus in on what is most important and clinically relevant instead of focusing on minutia,” she says.

While textbooks are a mainstay of any veterinary education, CVM faculty members also developed tools and methods to enhance their instruction, including two significant contributions by Cox and Fletcher.

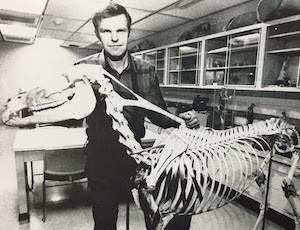

Cox joined CVM in 1975 as an anatomy professor. Initially interested in pursuing bovine medicine as a practitioner, Cox turned his focus to anatomy and teaching. That eventually led him to oversee CVM’s gross anatomy lab and pioneer techniques for increasing the learning value of anatomic specimens.

Because the “shelf life” of wet anatomic specimens is short, time invested in detailed dissection is lost when a wet specimen is discarded. Cox solved that problem by use of freeze-drying and plastination—a process in which the water in soft tissue is replaced by silicone plastic—to produce permanent, dry, nontoxic specimens that can be used and handled without gloves.

“These specimens are odorless, non-toxic, and permanent so their use is not limited to the anatomy laboratory,” Cox says.

While his colleague pursued creating a better specimen, Fletcher saw the opportunities technology presented in shaping anatomy instruction.

“Software programming caught my interest early, and I persisted in learning more of it as the technology evolved over the years,” he says.

During his time at CVM, Fletcher and faculty colleagues developed Minnesota Veterinary Anatomy (http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu), an umbrella site that encompasses about two dozen individual courseware websites/apps focused on anatomy instruction. To this day, the courseware is offered freely to the international community. In 2021, courseware home pages received 200,834 visits from 185 countries.

As technology advanced through the decades, the College’s anatomy team saw opportunities to adjust its instruction methods and adapt to changing student expectations, according to Dr. Tina Clarkson, an associate professor who spent 23 years teaching anatomy at CVM.

“Technology has dramatically changed and will continue to change,” she says. “Changing the way we teach is a gradual process, we cannot expect to keep up with the changing technology. We can, however, look at the educational research and be willing to adopt changes that have proven successful toward improving student learning outcomes.”

One such technology shifting anatomical instruction is medical imaging, such as computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning. The images produced by medical imaging make anatomical learning more efficient, according to Cox.

Cadaver dissection has been part of anatomical studies since ancient times and has long been a staple of both human and veterinary medical education. It too has seen a reduction in curriculums over the decades. Advancements in technology have allowed for the 2-D and 3-D re-creation of specimens and have seen success in courses. How much this part of veterinary education can be reduced remains to be seen, but Cox says cadaver dissection still provides students with an opportunity to practice valuable motor skills that can prepare them for surgical courses.

Teaching models also have adapted to include new tech, inspiring a hybrid style of teaching that engages students in person and over video calls. This “flipped classroom” allows students to view lecture-type materials online prior to class sessions. Video call sessions are offered to complete active learning activities, review difficult material, and answer students’ questions. Brown also has created dissection videos and dissection eBooks for their written instructions that students follow in dissection labs.

By the time students come to the lab, they can jump right into performing the dissection.

“We feel these are positive changes that offer more flexibility for the students and help to accommodate various learning styles,” Brown says. “Technology has been key in helping us develop and efficiently deliver our content and resources.”

Gross anatomy instruction will no doubt continue to shift as new technology and tools become available, but faculty and staff will continue to adapt to meet the College’s mission of educating current and future veterinarians and scientists.

“We are very fortunate at our College to have faculty eager and willing to embrace change,” Clarkson says. “Faculty and technicians are dedicated to improving student outcomes, engagement, and well-being as they take on the challenge to learn anatomy.”

The 2022-2023 school year marks the 75th anniversary of the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine.

Join us as we revisit milestones and innovations in the College's history and look forward to our future success in advancing veterinary medicine through teaching, research, and service.