Learning by doing

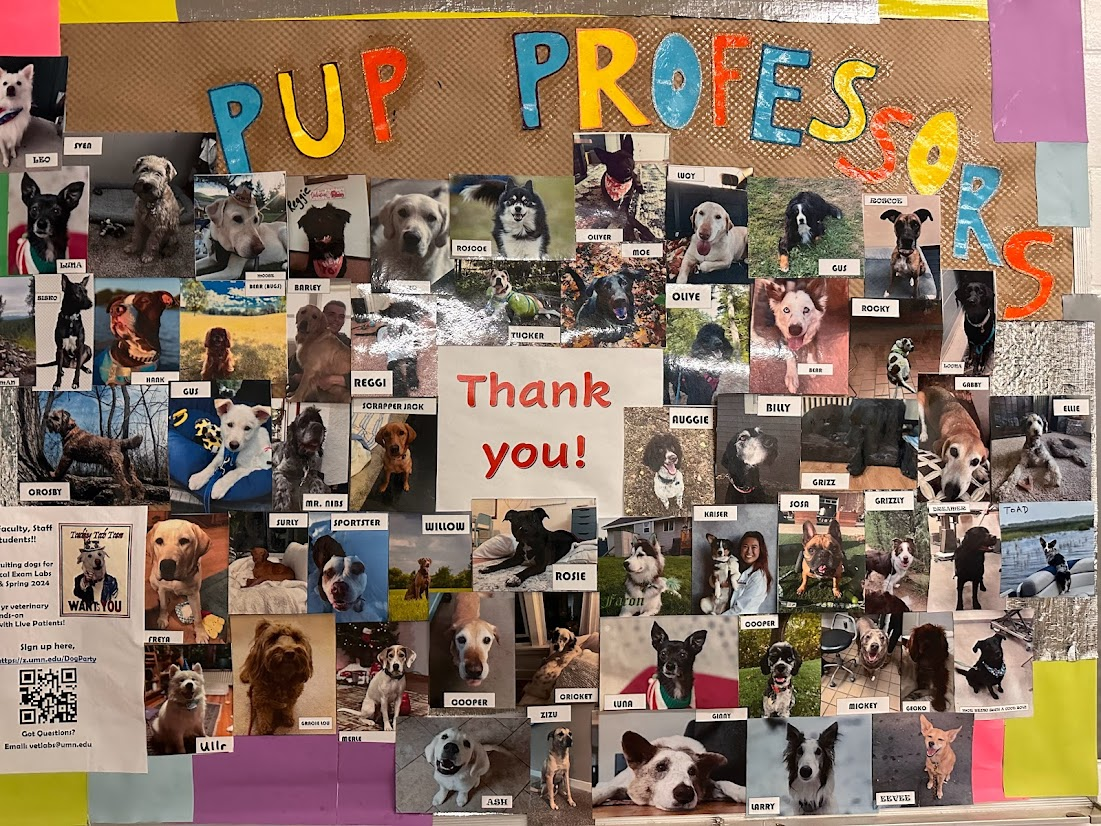

Pup Professors program brings together DVM students and volunteer dogs to practice exam skills

Pup Professors program brings together DVM students and volunteer dogs to practice exam skills

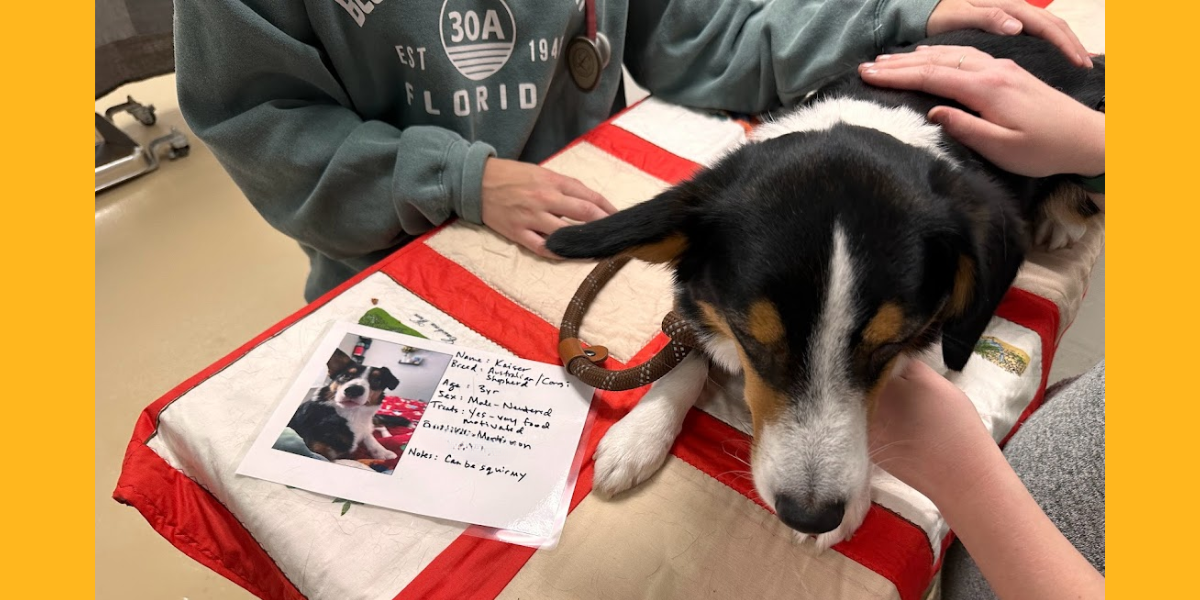

Pup Professor Kaiser lays on the exam table for a head-to-tail exam.

In a clinical skills classroom at the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), small groups of first- and second-year veterinary students gather near exam tables. Excitement and nervous energy fill the air as they wait to meet today’s “Pup Professors”—a corps of volunteer dogs playing the role of patients for the hour.

A group of skilled veterinary technicians, the Technician Teaching Team, manages the Pup Professors program and other clinical skills labs within CVM. The participating dogs, typically pets of CVM faculty, staff, or students, will receive nose-to-tail physical exams by students practicing their skills under the guidance of clinical faculty and house officers (residents and interns). Students have been preparing for this experience by attending lectures on dog handling and behavior, studying the physiology and anatomy of dogs, and reviewing videos demonstrating how to complete a physical exam.

Today is the first formal opportunity for students to practice the nose-to-tail physical in a clinical skills learning center with a live animal. Among them is first-year student Sophie Ramirez, who worked as a veterinary technician before starting veterinary school but never completed a full physical exam on a patient. Now, Ramirez is eager to put some of the skills she has learned in the classroom to practice on a pup professor in a real-life setting.

“I believe the pup professors will help prepare me for future clinical work,” she says. “It helps inspire confidence and allows for practice, and we all know the adage that practice makes perfect.”

Nearby tables contain laminated checklists of physical exam elements to guide Ramirez and her peers. One visual aid demonstrates how to determine the body condition score and muscle condition score of a dog by comparing its build to a series of photos showing an ideal weight versus too thin or obese. The tables also hold a picture and description of the pup professor—listing the dog’s name, owner, and personality traits.

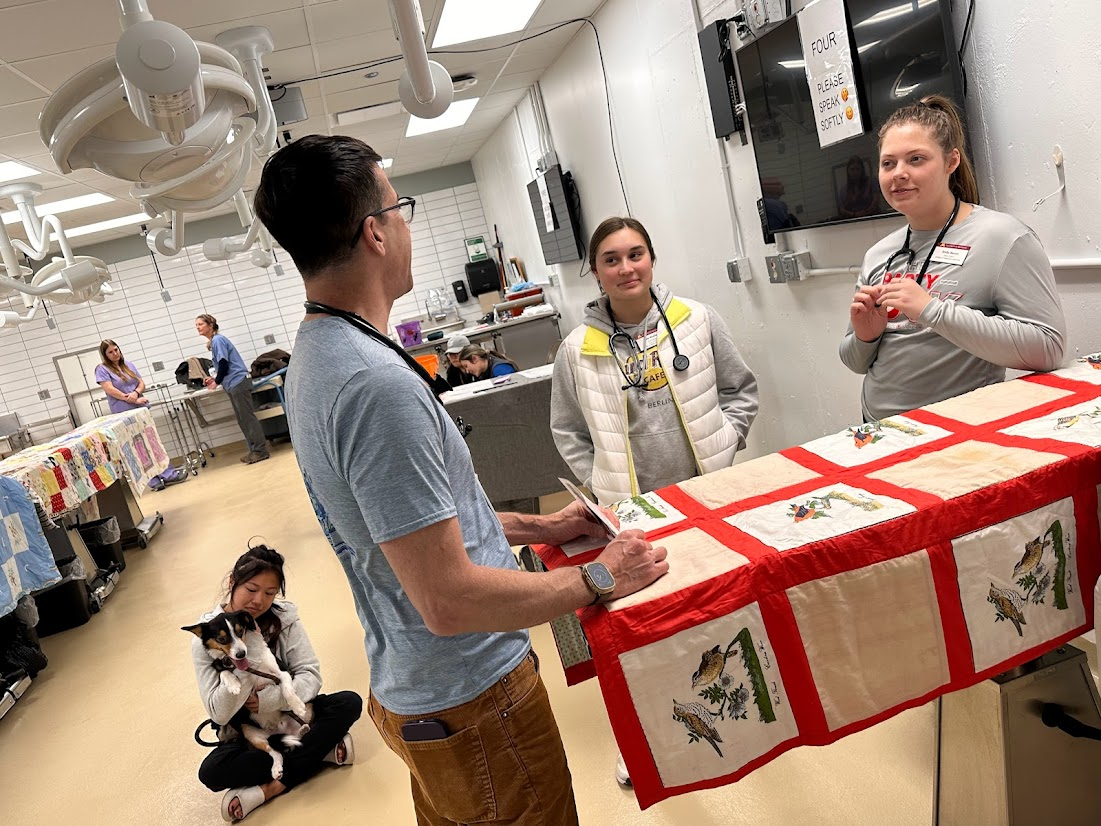

Instructor Dr. Steve Friedenberg, an associate professor in the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences (VCS), begins by reviewing techniques for conducting the nose-to-tail exam. He asks his student group what health information they observe about the dog from a distance. The students suggest the dog’s body language communicates behavioral cues such as relaxed, fearful, or anxious.

As their pup professor nears the group, Friedenberg encourages students to observe the dog’s gait and symmetry. After meeting and greeting today’s patient and hearing additional tips from Friedenberg, students take turns practicing physical exams. On the sidelines, he continues to guide the students with helpful suggestions or questions to facilitate learning.

Across the room, another instructor, Dr. Caitlin Yung, a veterinary oncology resident, demonstrates how to examine a dog's mouth to her students. Not long ago, Yung was in their shoes and learning these skills. She says the value of students working with volunteer dogs in this setting is “an opportunity to practice these skills in a risk-free environment builds student confidence and prepares them for the real thing.”

The physical exam is an essential skill when DVM students join the veterinary workforce. The American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges lists “gathering a history, performing an examination, and creating a prioritized differential diagnosis list,” as one of the foundations of its Competency-Based Veterinary Education program.

“Perhaps the most critical clinical skill for all veterinary clinicians is learning how to complete a thorough physical exam the same way each time and knowing what a normal exam finding is and what is an abnormal finding,” says Dr. Susan Spence, an assistant professor in VCS.

Students working with the pup professors also learn to use techniques that alleviate handling- and restraint-induced stress. The exam uses a Fear Free certified approach, teaching students to focus on what it takes for each pet to be comfortable during the visit by reducing fear, anxiety, and stress.

For example, if the pet is nervous standing on a stainless steel table, a non-slip pad and comfortable mat are used, or the exam may occur on the floor. The exam stops if the volunteer pet shows body language consistent with fear, anxiety, or stress.

The comfort and safety of Pup Professor participants is a top priority of the program’s facilitators. Because the program involves live animals for teaching purposes, it goes also through a University review board governed by the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee.

While it’s possible to teach some skills with simulators and models, these methods don’t give students practice in managing various behaviors encountered when examining a real dog accompanied by its owner. Working with the Pup Professor program volunteers offers students an opportunity to build confidence and competency in their skills and lay the foundation for providing quality care to their future patients.

The program allows students to practice their physical exam skills on many different dogs and experience guidance from a variety of clinicians so the students get a good variety of physical exam techniques and approaches. These skills can be directly applied when they start their fourth-year clinical rotations.

Pup professors and the clinical skills lab are crucial in training the CVM’s first- and second-year students. Educational spaces like the clinical skills lab provide invaluable experience to students as they prepare for day one on the job. The commitment to provide dedicated clinical skills spaces shows a commitment to graduating students prepared to enter the workforce confident in their ability to do the job.